Reflecting on Independence Day

I woke up this morning thinking about freedom and independence, not just because it is the celebration of the United States freeing itself from England, but also because it is the anniversary of my freeing myself to create my own business.

That was back in 1977 when I set up a personal consultancy focused on organization development, communications, and graphic & design. My logo was a bright yellow spot, looking a bit like a light bulb. Here’s the image. (Note: I don’t live on 6th Avenue any more.)

That was back in 1977 when I set up a personal consultancy focused on organization development, communications, and graphic & design. My logo was a bright yellow spot, looking a bit like a light bulb. Here’s the image. (Note: I don’t live on 6th Avenue any more.)

Looking back the feeling of excitement about declaring “independence” didn’t last very long. I wasn’t very “free” in those early days, in the ways that mattered most. Deciding to be “independent” I was also deciding to take on a new set of responsibilities. I now had to do my own marketing, selling, writing, fulfillment, invoicing, and all the other things that make a company a company. My little startup was really nothing more than idea, and the next three years were a slide into challenge after challenge as I struggled to figure out how to run a business.

I’d been working at Coro, a high minded non-profit whose purpose was to improve the quality of public process by training leaders in public affairs. I could make a great case for the ability of a small percentage of dedicated people being able to shift a system, and get grant and donation money to support our work. But business was a different thing. My new freedom required new responsibilities and new understandings.

As an independent consultant I had to figure out how to talk about what I could offer that people would pay me for, right away! The connection was direct and specific. “I can facilitate your meeting with graphics,” I could say confidently. But in 1977 who wanted that? It wasn’t the way anyone conducted business, except designers and architects and engineers. Other people talked, or showed overhead slides, or looked at numbers (not even spread sheets in those days). Who needed visual meetings anyway? I worked my network, and got odd jobs, but I wasn’t really taking off.

I remember the year I actually gained some independence and freedom, and it was when I figured out who really needed what I had to offer and began to book some serious business. It happened at a Group Graphic’s workshop at Fort Mason in the early 1980s. A Canadian strategy consultant named David Cawood attended. He had been as a big eight firm but preferred “independence” and was on retainer to several large Canadian firms as an assist to their management teams. He had the idea that I could come up and facilitate one of his more complicated meetings with graphic recording. He’d set it up as an experiment, and if it didn’t work, he wouldn’t lose anything. I just wouldn’t come back. But if it did work he would have discovered a way to differentiate his value from other competitors!

It was as if my little light bulb logo suddenly powered up! I get it. My clients could be independent management consultants, who already have work, and not the organizations themselves! Within six months I was working at the top of the house at Apple, General Electric, General Mills, and David’s client, Federal Industries, a conglomerate with businesses across Canada.

Later Arthur M. Young, the brilliant evolutionary theorist who articulated the Theory of Process that has been so inspiring to The Grove, provided an explanation of this phenomena – of why freedom without constraint really isn’t freedom. He saw all process in the universe as a marriage between phenomena that is very unpredictable and dynamic, like light and fundamental forces, and phenomena that is governed by rules of cause and effect, like molecules. The free stuff needs the constraint of mechanisms to express themselves, he’d say. It’s only when we learn the rules at the bottom line that we can turn toward the freedom we imagine in our top line aspirations. This kind of freedom comes from mastery—quite different than freedom that is simply absence of constraint.

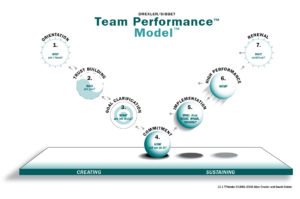

Year’s later my work with Process Theory and with Alan Drexler became the Drexler/Sibbet Team Performance Model.

It is the same idea. A team has no real freedom to get results as a team until they have oriented to their purpose, build trust, clarified goals and come to firm commitment about roles, resources, and direction. Then it can take off , turn a corner, and begin to implement.

This puzzle of things getting harder before they get better shows up in many other places. As someone raised in the East side of the Sierra Nevada mountains, I know that when you are on a peak and see another one off in the distance, the process of getting there means going down first, and often fighting through deer brush and losing sight of where you are going, before you can climb up again to that new peak.

Claiming independence is just the beginning of something. Our Founding fathers had to create a government. They struggled. They wanted to avoid the ills of monarchy, and the perils of popular democracy. They needed a balance against greed and poor quality, and out of their experiments came our courts, the two houses of Congress, and a President with much less power than a monarch. The system worked for a long time.

But we are on a fitness peak now that is under siege. Living high on the hog at the expense of the rest of the world is not true sustainability. Depending on extraordinary military expenditures to sustain this system seems difficult. So where will we find a new set of freedoms—freedom from terror, freedom from poverty in old age, freedom from being whipped by an economy run by micro-traders on super computers?

We are going to have to learn the new rules to have those kinds of freedoms not just declare them. This is the challenge President Obama faces. He declared freedom but he hadn’t earned it, in that his team hadn’t yet mastered the new rules of these times.

As I sit in my studio this July 4th thinking back on 33 years of business, I do have considerable freedom. But I face a new mountain peak—that of being an elder to my generation and the next and the next. What do I really know about this role? How much of what I have learned applies to these times? How receptive are the younger people? How, in a time of multi-tasking and instant gratification, do we learn that you can’t rush learning the disciplines of agriculture, the time it takes to have and raise a baby, or the amount of time it takes to grow truly new understandings between our ears?

Independence and freedom, the kind that Michael Jordan had on the court, and Thelonius Monk had on the piano, comes with practice with and acceptance of constraints. It’s that dance that I celebrate today! It’s that dance I intend to engage the rest of my life.

No Comments