What’s Our Edge? A New Year’s Question

The time between Christmas and New Year’s always beckons me to think about what is emerging in my life. The ceremonies during the holidays are clues – which decorations call for attention? What kinds of rearrangements in my desktops and altars mirror what I am working on? How do my dreams pull in themes? Where do I find myself moving in conversations with colleagues?

The time between Christmas and New Year’s always beckons me to think about what is emerging in my life. The ceremonies during the holidays are clues – which decorations call for attention? What kinds of rearrangements in my desktops and altars mirror what I am working on? How do my dreams pull in themes? Where do I find myself moving in conversations with colleagues?

This year the voice of my now deceased wife Susan talking about Gertrude Stein grabbed my attention. Over the holidays I spent considerable time getting some tapes of Susan’s poetry readings digitized. Included was a panel talk about Stein. Her co-panelist was asserting that Stein was celebrating streams of consciousness in her poetry, which to him didn’t make much “sense” in an intellectual way. “ How ironic you should say that,” Susan said. “All of her work was about waking people up – bringing people to a kind of fresh listening by very consciously and systematically interrupting normal interpretive patterns. Her work was the farthest possible from streams of consciousness.”

Stein and her European friends, notably Pablo Picasso (who painted the portrait of Stein shown here) were consciously out on the edge in their times, using image and language to wake people up, see and hear differently. I’ve always admired their courage and contribution. “What is our edge in this time?” I began to wonder. What are we consciously trying to manifest?

This question came up recently when my colleague Gisela Wendling and I were talking over lunch out on the deck at Apple Box, by the Petaluma River. The day was crystal clear and crisp. We are working together on catalyzing The Grove network to become more of a learning community, to hopefully support each other as we tackle the big problems of our time that need facilitation and consultation on change. “What is our edge?” I wondered?

Seeing Connections

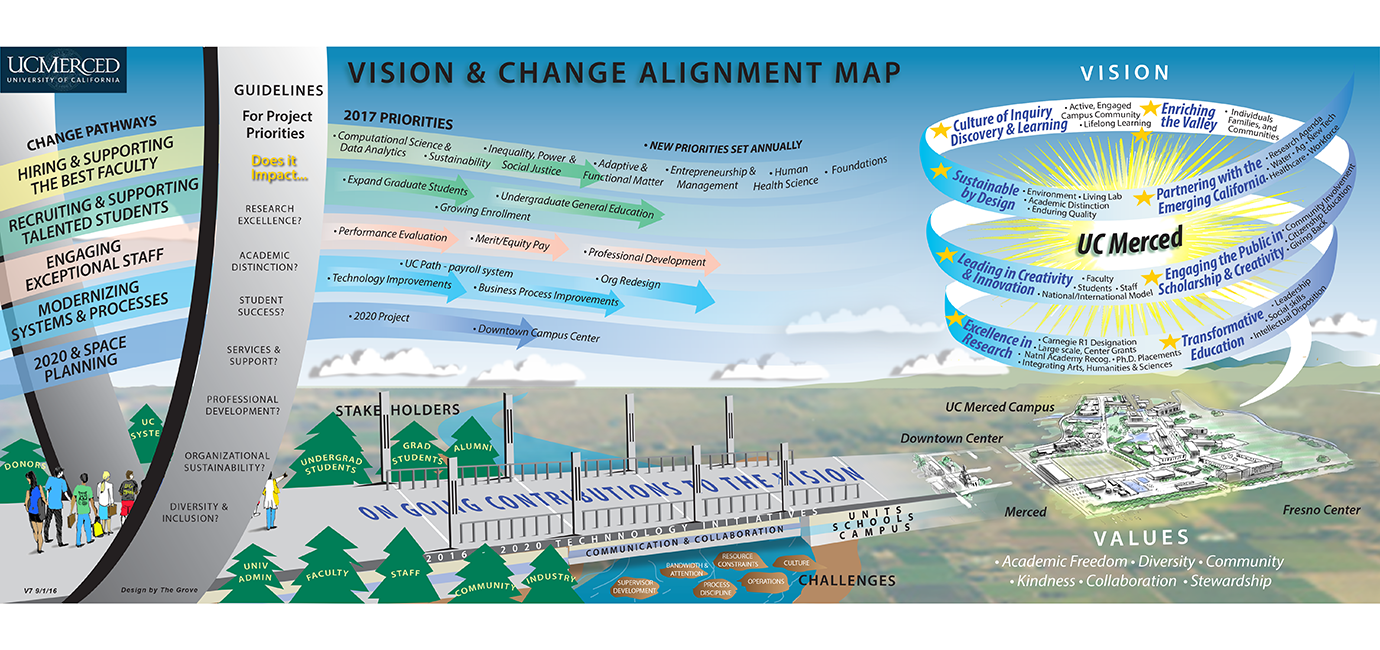

Even as I asked the question a response started forming-“connections – seeing connections!” I said. Years of work with visualization have led me to believe it is our visual sense that provides a foundation for sensing how whole systems work. Last year I helped Gisela on the “Crises to Connectivity” report for the California Roundtable on Water & Food Supply, a project of the Ag Innovations Network, on this subject. The Roundtable, a group of senior leaders from many different sectors that she facilitated over several years, determined that the edge in their field was “Connectivity.”  They identified the need to link ideas and connect people and institutions and move toward a sense of “connected benefits” rather than individual interests. Of all the work going on in regard to water and food, they felt the lack of a holistic, systemic perspective was the most urgent. This idea has grown like a seed in my own mind after helping with the graphics.

They identified the need to link ideas and connect people and institutions and move toward a sense of “connected benefits” rather than individual interests. Of all the work going on in regard to water and food, they felt the lack of a holistic, systemic perspective was the most urgent. This idea has grown like a seed in my own mind after helping with the graphics.

As we talked by the river, we also started reflecting on the limits of visualization. After so many years of doing visual facilitation, I’m quite aware of what it doesn’t deal with. “Seeing” and “mapping” let us understand connections, in what my Process Theory teacher Arthur M. Young called “formed space”—the physical world of objects. It’s also very helpful at the conceptual, intellectual level of how we make sense of things with words, images, and numbers. But what about the energetic realm, and that which emerges in-between people when they are engaged in thinking together, and what about intention – all nonobjective yet very important parts of the human experience?

An increasing focus in my work is looking at how the process of mapping generates felt experiences of connecting. I believe these strong experiences are then carried in the somatic memory of groups and people, growing their felt sense of being part of a community and organization. Gisela agrees. Her research suggests that one of the most important competencies in cross culture work is to be able to build a “living bridge of feeling” between people at the energetic level. Is intellectually seeing connections without this feeling enough? We don’t think so. It takes an immersive, experiential bridge.

Doing Collage

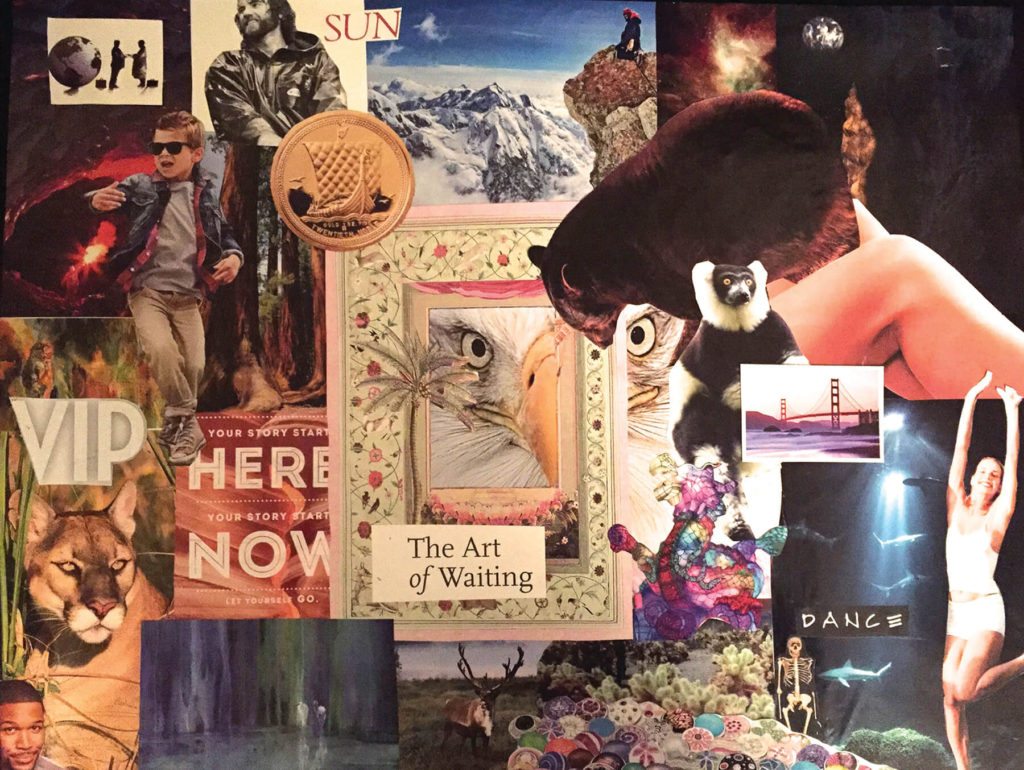

Later in the day Gisela and a close friend, Jennifer, and I met to create collages that reflected our experience of 2014, as a way of closing out the year. These collages are maps of a sort. Selecting the images was a kind of thinking and clarifying process. But sharing the images as we worked separately, and then sharing themn again through our stories and associations as a group, deepened our own connections on energetic and intentional levels, well beyond visual, conceptual levels. It reinforced my sense of how powerful co-creating visual images can be. As rich as the artifacts themselves often are (see below) , the associated stories and meanings are the real content, and this only emerges in dialogue.

And then there is the great mystery of meaning. There is no accurate way you, the reader, can know what I personally associate with these images, and even more mysteriously, what I personally feel when I look at this image and imagine and remember last year. Your meaning will arise from your experience. Without real talk and connection, the artifact will only be valuable so far. How true this is of many of the other images we create at work.

After dinner I asked Jennifer the question Gisela and I were discussing that morning. “What’s our edge” in these times? Her answer surprised me.

Autumn of the Empire?

“The twilight of capitalism,” she said simply. “It doesn’t work any more for most people; it’s killing the planet; it ignores deeper values of community; it’s all about profiting and taking advantage.” Her answer rocked me. So clear; so matter-of-fact.

I immediately thought of the LA Times book review written in 2011 reflecting on the crash of 2008 titled “The Autumn of the Empire.” It was written by Joshua Clover and reviews four authors that are looking big picture at the history of Capitalism. Again without reviewing this article (which is well worth a re-read if you’ve seen it), authors trace the expansions of four big historic capitalistic systems and see a pattern. Trade drives the initial expansion, then the driver becomes manufacturing, and in “the autumn” of each period, finance comes to drive the economy. The evidence seems abundant that we are in this phase.

“I appreciate the irony of saying this,” Jennifer continued. “We’re both business owners.” How true. But she was talking about the mental model of big “C” Capitalism as an ideology, not the grounded experience of a small business person. Clear trade is a good thing, but as with anything, good things can shift value in the extreme. Today the “system” of Capitalism legally and socially promotes the value of profit-taking and market dynamics, seeming above all other values. Yes there is a blooming “conscious Capitalism” movement. But the dominant system leaves the commons, small stewardship-oriented operations, mothers who don’t work in order to raise children without pay, and many other valuable elements of life stranded without support.

Jane Jacobs, best known for Life and Death of Great American Cities, a seminal book in urban planning, wrote a relevant but not well known book in 1992 called Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics. Her characters, in a salon on the East Coast, explored the fact that humans as a species have two ways of surviving. The first is hunting and gathering – being stewards and guardians of common resources. The second is exchange and value adding in the way the trader. Both have very different systems of values that support them, and are not especially compatible, according to her. In fact, very confusing and ineffective things happen when you ask market valuing people to take over guardian valued roles and responsibilities. I won’t summarize the arguments here, but both approaches can be businesses. It’s just that the trader approach, now elaborated as capitalism with a capital “C”, doesn’t really value stewardship. It anthropomorphizes enterprises and provides legal structures benefiting capital, with little or no attention to the need for stewardship of common resources, like the atmosphere. Ironically most of these big businesses are heavily subsidized by government, an inherently “guardian oriented” institution, and they are considered to have free speech (including media) like all citizens. How far have we moved toward a de facto oligarchy, many wonder?

Jane Jacobs, best known for Life and Death of Great American Cities, a seminal book in urban planning, wrote a relevant but not well known book in 1992 called Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics. Her characters, in a salon on the East Coast, explored the fact that humans as a species have two ways of surviving. The first is hunting and gathering – being stewards and guardians of common resources. The second is exchange and value adding in the way the trader. Both have very different systems of values that support them, and are not especially compatible, according to her. In fact, very confusing and ineffective things happen when you ask market valuing people to take over guardian valued roles and responsibilities. I won’t summarize the arguments here, but both approaches can be businesses. It’s just that the trader approach, now elaborated as capitalism with a capital “C”, doesn’t really value stewardship. It anthropomorphizes enterprises and provides legal structures benefiting capital, with little or no attention to the need for stewardship of common resources, like the atmosphere. Ironically most of these big businesses are heavily subsidized by government, an inherently “guardian oriented” institution, and they are considered to have free speech (including media) like all citizens. How far have we moved toward a de facto oligarchy, many wonder?

As I mulled over these kinds of questions, I also found myself reading Gregory

As I mulled over these kinds of questions, I also found myself reading Gregory

Bateson’s post humous book, Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. It was written in 1991 and reissued last year. In thinking about anything important, Bateson cautions against trying to be too rational and objective, knowing that language of all sorts—reflected as laws, maps, and ideologies—all fall short of touching the full sweep of consciousness and the human condition. Language requires distinctions. Distinctions lead to seeing things as separate entities. Separation leads to competition and conflict. And mythos of separateness and competition underlies it all. This may be the dark stepchild of rationalism. What alternative leads to connection and cooperation? I don’t think it’s an accident that businesses themselves are reaching out for engagement, mindfulness, interdependencies, customer intimacy and the like. I think like any organism, they are reaching out to balance an out-of-balance system.

This line of thinking also led to remembering Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone, an exploration of the collapse and revival of the American community (2000). He explores long term data on social affiliation, extrapolating that time spent in groups and with each other creates social capital in a community. (There are more bowlers but less club bowling—hence the title). He correlates high levels of social capital with other data and shows it correlates with better health, education, and other community values. He also traces the steady decline in affiliation activity since 1975 (as much as 40% he claims) and points to TV and commuting as the culprits. In hearing him present on this idea at the Commonwealth Club some years ago I remember him speculating about whether or not social media and increasing “connectivity” represents a hopeful revival. He said that depends on whether or not these systems are entertainment, or real connection. That question still isn’t clear. So another question weaves into this reflection on connectivity. Will our social media environment build real bridges of feeling, or be just another stimulus, like caffeine and action movies?

This line of thinking also led to remembering Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone, an exploration of the collapse and revival of the American community (2000). He explores long term data on social affiliation, extrapolating that time spent in groups and with each other creates social capital in a community. (There are more bowlers but less club bowling—hence the title). He correlates high levels of social capital with other data and shows it correlates with better health, education, and other community values. He also traces the steady decline in affiliation activity since 1975 (as much as 40% he claims) and points to TV and commuting as the culprits. In hearing him present on this idea at the Commonwealth Club some years ago I remember him speculating about whether or not social media and increasing “connectivity” represents a hopeful revival. He said that depends on whether or not these systems are entertainment, or real connection. That question still isn’t clear. So another question weaves into this reflection on connectivity. Will our social media environment build real bridges of feeling, or be just another stimulus, like caffeine and action movies?

The Grove’s Edge

Through this line of thinking (and writing this blog piece) I’m emerging with a better sense of “the edge” for The Grove this coming year. It’s bordered by questions. Can we bring the experience of co-creative process not only to our meetings and change processes, but also to our virtual work? Can we celebrate the full sweep of human sensibility as we work to make sense of our times with visuals? Can we complement the considerable value of “seeing connections” with helping people and organizations actually “feel” their connectivity, not only with each other but also the natural world? Can we support our Grove network coming to a lived sense of being interconnected? These seem like great questions for edging into a new year.

No Comments