The Postmodern Challenge

My struggle to make sense of this new era of Trump has sent me back to my journals to look for longer threads and themes. I’m having an old feeling. It’s one I associate with the time of the assassinations in the 1960s, the lying during the Nixon and Johnson years, and the warmongering of the Bush years. In such times of disruption in my mental model of a world that progresses—carefully inculcated by my post-war teachers—I am thrown into questions.

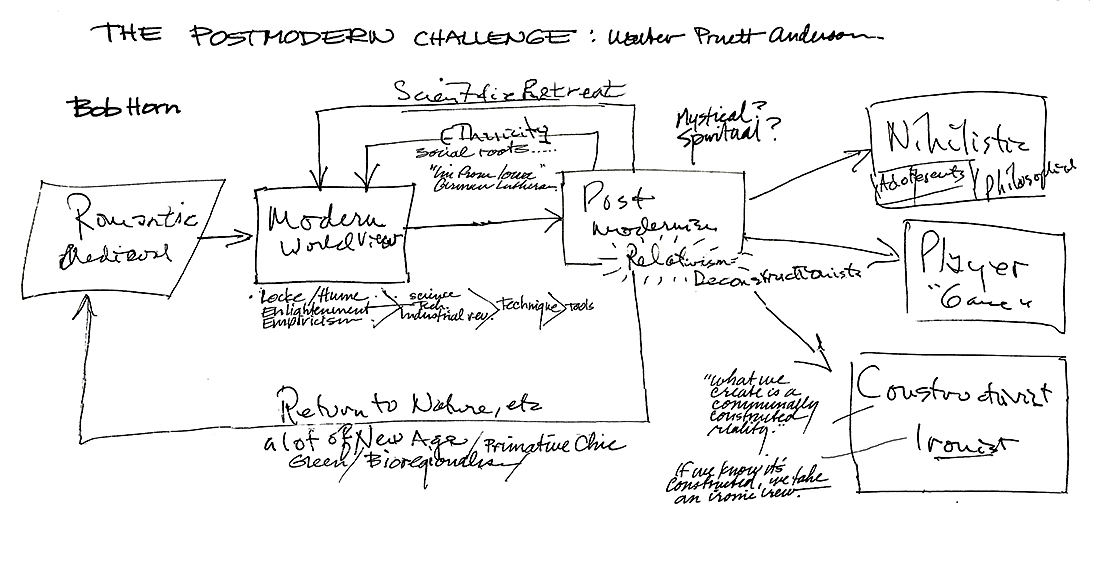

Finding myself back in the questions again, I came across a journal entry from December 1994, recounting a talk with my friend Bob Horn about postmodernism. Our talk began with a review of Walter Truett Anderson’s schematic of the postmodern challenge:

As Bob drew the boxes, I had wondered at the casualness with which he could lay down a box and label it “postmodernism”, as if all the perceptions and theorizing and turmoil of the times could be neatly packaged in a historian’s bow. “I won’t say anything,” I thought. “I’ll listen past it to the meaning.” Meanwhile, in my own mind I began to frame a story of fragmentation and return, of choices and confusion.

We talked of “context.” Stewart & Cohen’s book Collapse of Chaos has given me some language for looking at modern thought. I find I can make sense of some of this if I consider scientific inquiry, and the search for theories of everything, as the leit motif of the 1900s when science and scientism became the norm for respectable thinking. Scientists embraced laboratory learning as a key to the mysteries, leading steadily toward less contextualized formulations being lauded as the “laws of nature.”

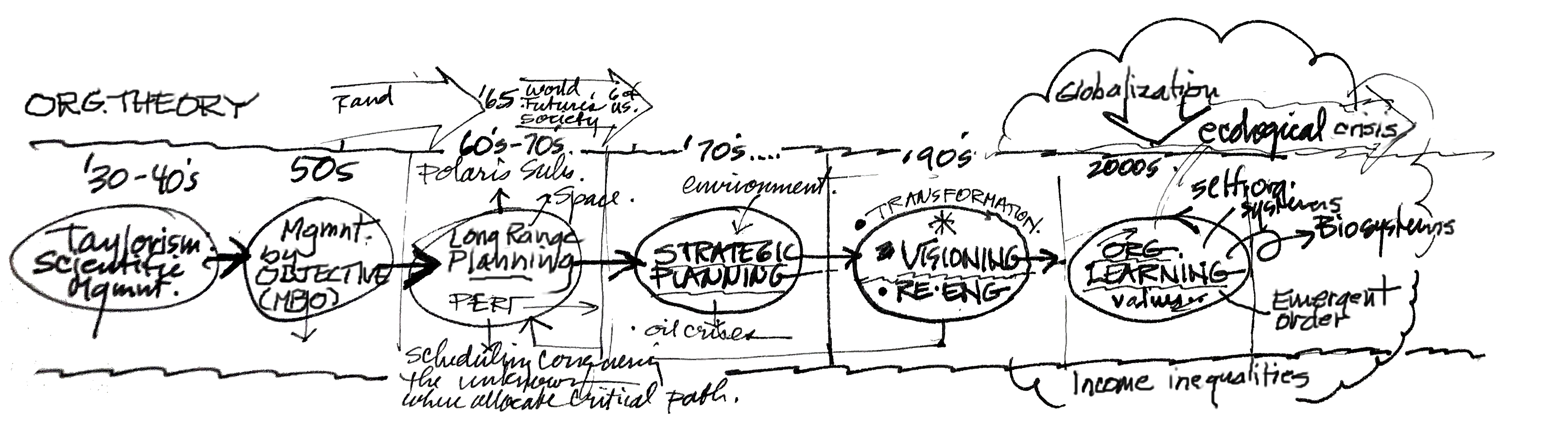

Bob and I then looked at the development of organizational theory through the postmodern lens, speculating on the reasons for strategic planning’s popularity in the 1970s.

Why did environment & context become so important at that juncture? I surmised that the uncertainty of the late ‘60s, the oil crisis, and the allure of reductionist thinking had reached a dead end. Also, the flood of data from new tools and instruments was outstripping the old paradigms.

World War II, terrible and chaotic as it was, was accompanied by a sense of moral certitude that aligned people in a shared focus on action and problem solving. Back then there was little confusion about our core story: America was saving the world for peace. (As that story faltered, the need for strategy grew.)

Now our stories rot in the barnyard of media, stomped, eaten and regurgitated like social cuds. We grimace at the latest crime stories at the same time our hungry eyes beeline to the familiar and the bizarre.

“I want to work to keep the bigger stories from being lost to the smaller ones!” I said. “It’s a small story to figure out how to sell the next gadget more cheaply than a competitor. (And how to win personally, I now realize.) It’s a big story to imagine the unleashed power of diversity and organizational learning.”

Now, 22 years later, I’m aware that as upset I was back then about the disruption of our core story, I couldn’t have imagined our current situation. The postmodern challenge I sensed then is even bigger. But interestingly, the efforts to forge a new narrative do fall into Bob’s three postmodern buckets. Judging from many new movies, the apocalypse is near and dark, and nihilistic narratives grow steadily on the Internet. Based on our new president and press secretary’s speeches, gaming the system is acceptable and even hailed as “smart” as long as you win. I’m in the third bucket: working to help a constructivist story emerge.

I want to believe that those of us who care about public service, community, children, families, income equity, respect for indigenous cultures, and sensitivity to the impact of actions on others will learn how to share and amplify a new narrative. I hope it embraces these values and provides enough constancy to inspire and sustain new institutions, like the collaborative network we are calling the GLEN (Global Learning & Exchange Network). This is the work that calls me to action. This is our postmodern challenge.

Robert James Smith

April 11, 2017This particular blog prompted me to get and read Reality Isn’t What It Used to Be, while holidaying in Florence Italy. It is indeed a thought provoking book with pointers to progressing in our current age. The need to reflect, consider and evolve contradictory belief systems particularly struck a chord. In Florence, one of the centers of the Renaissance, the Medici family apparently managed to be bankers to the Pope, while supporting science, including Galileo and religious art. I hope our progress in evolving socially constructed reality is as innovative as the Renaissance, without the shadow side ruthlessness.

David Sibbet

January 29, 2017Dear Nancy

Writing this blog sent me back to the source, Walter Truitt Anderson’s 1990 book, Reality Isn’t What It Used to Be. It’s hard to believe its 26 years ago he wrote that, but was quite prescient about the world we are heading into where truth is fungible. I’m reading it carefully to try and think around the easy polarity he describes–between literalists and constructionists. This is a very different schism than between left and right, or different religious sects. It’s a difference that cuts across the other differences. I do side with him that there is no turning back to literalism as a widespread world view. It just doesn’t stand up against the experience of being in a globally diverse and circulating-across-bondaries world. It does look like the fundamentalists are going to have a swing at leadership for a bit, but for that kind of stance to truly work it needs less variety in the context in which we live. It’s no accident the more heavily populated coasts are more blue–Hillary’s kind of pragmatic blue. I don’t have answers, but my inquiry is about the kind of thinking that can hold deterministic patterns and patterns of uncertainty within the same system. I find this pairing in my current jazz piano lessons, where the deep discipline of keeping the beat and knowing what chords you are playing in what forms (blues, rock, etc.) allows the improvisation. Constructionist stances need certainties to push off from to be generative. There will be a global culture. There is already. But it is really in an early stage. Our great grandchildren will look back and marvel at all we though was “true” in our times.

Nancy Near

January 27, 2017I am reading “Dark Money” by Jane Mayer now, and it’s leaving me feeling a little hopeless about the Constructionist bucket. How can we stand (and grow) against all the money and the disdain for fairness & rules of law that make up the opposition? Do we end up using the same tactics? Help me Obi Wan — you’re my only hope!