Jan 04, 2021

Jan 04, 2021h

in

Cognition & Communications,

Collaboration Strategies,

Global Learning,

Inspiration,

Leadership,

Leading Change,

Mental Models,

Personal Transformation,

Process Theory,

Social Change,

Sustainability,

Systems Theory,

Transformational Leadership

by David Sibbet

Photo by Alan Briskin

“Earth’s creatures are on the brink of a sixth mass extinction, comparable to the one that wiped out the dinosaurs. That’s the conclusion of a new study (by paleobiologist Anthony Barnosky of the University of California, Berkeley), which calculates that three-quarters of today’s animal species could vanish within 300 years.” From Science Magazine: Ann Gibbons, 2011.

At the beginning of this year the sixth extinction came to me in a dream. I was at a gathering of about 15-20 colleagues in a conference center that included many other people. We were getting to know each other with introductions. After some swirling around eating and getting set up so we could talk it was my turn. I stood up and found myself saying “I am a professional facilitator and am currently focused on the sixth extinction. I want to help bring forward the new ways of thinking and behaving that will be required to survive it.” I remember feeling surprised in my dream at what I was saying, but continued. “You will get to know me as someone who both draws and listens, guiding people to visually design processes that allow them to change, adapt and think more ecologically.”

At this point a young man rose up and said, “I was at an institute recently where someone was doing that, and the charts zig-zagged all over the wall. It felt like a breakdown.”

“That is often what happens when people look closely at their own thinking and information,” I said. I should be flummoxed I thought, but I felt calm and grounded. “It is this breakdown that allows them to break through.”

The group applauded! I was surprised and my heart was racing. I sat and turned to a young man sitting beside me and said, “this is the first time I’ve ever introduced myself this way!” I remember I was feeling both startled and strangely alive and excited. And then I woke up. I knew I needed to pay attention to this dream.

It was 7:05 Sunday, the last day of a long holiday break that my partner and I described as our “digital vacation”—no Zoom, email or social media. Because of the pandemic, and a steadily worsening number of cases along with the news that a more viral version was already spreading in California, we cancelled a trip to a local hot spring where we hoped to have some renewal time, and instead stayed home. The renewal idea carried over and we treated our home as a retreat center.

There I had time to link this dream to some earlier faint signals.

Tracking Back Through Journals

At a GLEN Community Winter Solstice Gathering call before our holiday week started, Karen Wilhelm Buckley, a colleague, read a poem I’d written at a Summer Solstice gathering of colleagues in 2004. I had no memory of it. So, I went back to journal number #134 and there it was. (Journaling is one of my reflective practices). The poem was about the group and our process, but the journal had some other very important entries that were connected to my dream.

I realized that 2004 was the year I turned 60. This was a real milestone at the time, and I had planned several “rites of passages” for myself to mark the change. It began with a week with my first wife Susan (now deceased) to visit the half dozen vision quest sites I’d experienced on the East side of the Sierras (where I grew up).

Later in the summer I had then planned for and gone on a new vision quest on Mt. Shasta with my teacher, Chayim Barton, and a small group. I was rocked to see here I had written about one of the most significant visions of my life up to that point. I think now that it was the headwater of my dream.

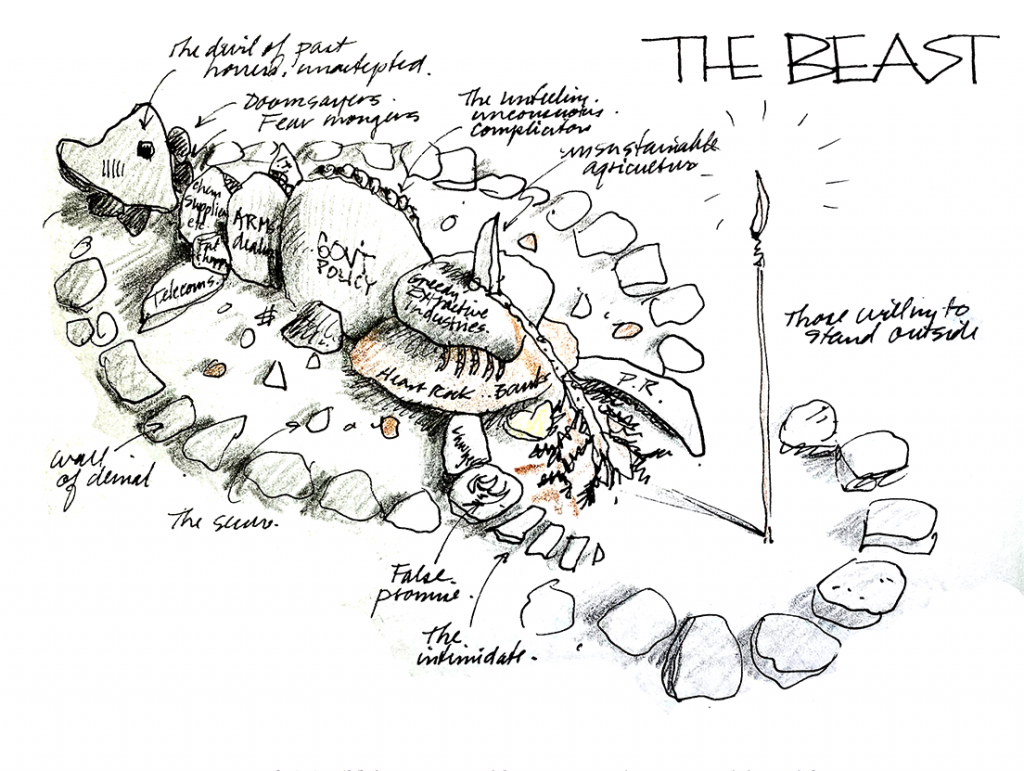

Facing the Beast: Prior to the Shasta quest, I’d been being “worked” by an upset feeling about the dominance of “extractive” industries that pay no attention to biology, local communities, or the hidden costs of their work. “Why don’t you work on it here,” Chayim suggested as he counseled me before heading out on a three-day solo water fast. He invited me, in my solo time, to build a monument to this “beast” as I called it, reflect on it, and practice Tong-Lin (a Tibetan practice where you take in pain and breath out compassion), and then take the “beast” apart as a conclusion. I took this suggestion and on the second day of fasting created a monument. Here is my journal drawing with the associations labeled. I don’t need to describe my full process here but can easily remember how powerful it felt. Building it took many hours. So did disassembling it. It was easily 8 feet long. What deeply disturbed me was my grasping experientially the extent of the systemically embedded exploitation mindset. But more disturbing was trying to imagine what could stand up to it—represented by the little wand with a feather. After hours of circling and meditating and just sitting and writing about this experience, I ended up writing some of my core values on the wand—things like the golden rule, my Bodhicitta vow to serve the awakening of all sentient beings, and staying tuned to the light, and the source of vitality I find in embracing and respecting all life. But I hardly felt resolved about this.

I don’t need to describe my full process here but can easily remember how powerful it felt. Building it took many hours. So did disassembling it. It was easily 8 feet long. What deeply disturbed me was my grasping experientially the extent of the systemically embedded exploitation mindset. But more disturbing was trying to imagine what could stand up to it—represented by the little wand with a feather. After hours of circling and meditating and just sitting and writing about this experience, I ended up writing some of my core values on the wand—things like the golden rule, my Bodhicitta vow to serve the awakening of all sentient beings, and staying tuned to the light, and the source of vitality I find in embracing and respecting all life. But I hardly felt resolved about this.

Stepping up to RE-AMP

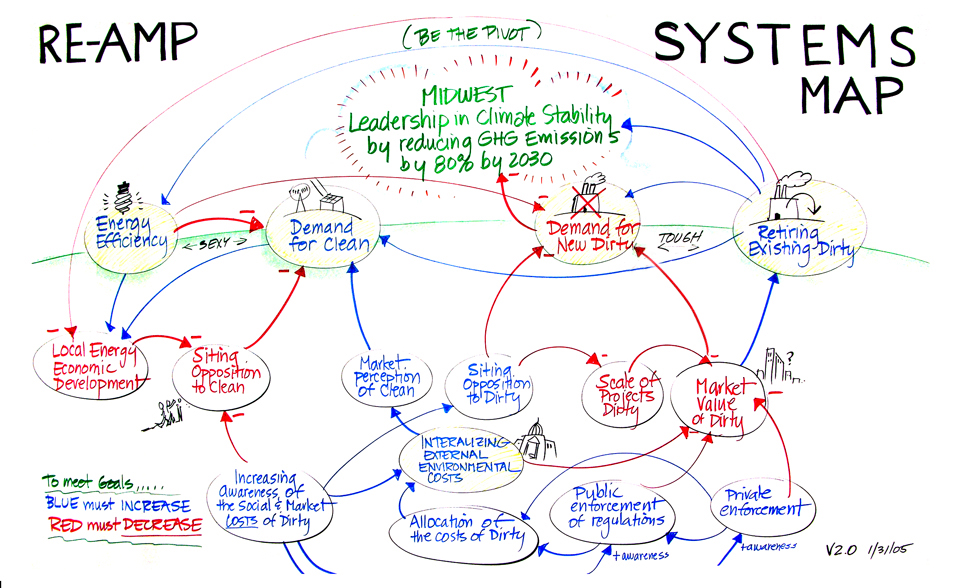

Later that year in December, I was asked to facilitate a new environmental organization called RE-AMP in the upper Midwest. The name stands for the Renewable Energy Alignment Mapping Project, initially a group of 25 environmental non-profits and 12 foundations, who, discouraged by results to date, wanted to work collaboratively to support the growth of renewable energy. They concluded that they had to work on four fronts in a systemic way.

- Reduce the impact of coal pollution from the 70 plants in the eight-state region

- Stop the construction of new coal plants (34 were in the pipeline)

- Increase energy conservation

- Increase renewable production.

The consultant who had helped create a causal-loop system diagram of why renewables were not taking off had concluded that these factors were all inter-related and needed to be dealt with in parallel. They needed a facilitator to help create the strategies of the four working groups.

At the meeting where the consultant, Scott Spann, handed off the project to me, he presented his system analysis in a series of complex slides, moving from a 175 factor causal loop diagram he had vetted with many experts, to a 16 factor overview diagram (Shown here) to his conclusion there were four leverage points.

At the end of his presentation, he turned to the RE-AMP steering committee and, and speaking very deliberately, said – “Just remember, this is a MINDLESS BEAST.”

I can still feel the goosebumps. Oh my. Here I was standing in front of it again. The small stream of intention started on my vision quest was suddenly here, embodied, and real!

I and my company, The Grove Consultants International, spent four years working with RE-AMP with the agreed-on goal of cleaning up global warming pollutants in the eight-state region by 80% by 2050. The goal was not considered practical. But everyone involved believed anything less wouldn’t matter.

- RE-AMP did stop the coal plants.

- It didn’t get far on cleaning up old coal.

- It did stimulate energy conservation in the region.

- It encountered roadblocks regarding developing wind energy.

And it expanded to more than 150 participating organizations and over two dozen foundations “thinking systemically and acting collaboratively.” It is one of the most successful environmental collaboratives in the country and still it is not enough. The full story is for another time. Reflecting back, I realized it was my strongest experience so far of being moved by a vision without knowing the outcome. Would my sixth extinction dream might have this same arc of enactment. It feels HUGE! But then so does is this new “beast.”

A Calling?

I wondered why had my reflective “vacation” over the holidays had started with this retrospective. By accident? It was not “planned.” What guided that impulse? What was my psyche through my dream trying to tell me about what I should be doing with my work?

I remembered as I reflected that for several years now when asked about my core motivation—my life purpose— I’ve found myself saying that it is to “help midwife the coming ecological paradigm.” I perceive that we are in a shift that historians will eventually compare to the Copernican revolution—moving from engineering oriented/materialistic thinking to a more biologic, open systems approach, which will include but transcend the old paradigm, as new ones do. I also suspect that the shift will take years or centuries, as all such shifts have taken historically, and while already emerging in many places is hardly dominant. “We will live into this new way of thinking and relating, or we won’t,” I can remember saying in various workshops. To evoke a birthing metaphor, I feel that these last few years, with global warming directly impacting my home state of California in the form of volatile weather and fierce firestorms, that the baby of this new paradigm is crowning. It needs help.

And then I remembered that two weeks later I was clobbered by an interview article in the Sun Magazine with Eileen Crist about her new book, The Abundant Earth: Toward an Ecological Civilization. She is an associate professor at Virginia Tech in the Department of Science, Technology and Society and has written extensively about biodiversity and the mass extinctions taking place. I have been reading about this for years. But Crist’s reflections on how much more serious the extinction process is than the pandemic got through this time. “It takes 5-10 million years to recover the same levels of biodiversity” she wrote.

I know that reading information doesn’t really change me. But having a full, integrated systemic embodiment of the understanding at a feeling does (like the vision quest experience) and I was having that feeling reading this interview. I suspect it is because the pandemic is no longer an abstraction. I feel the losses deeply. Perhaps it ignited the same feeling about the extinction. I ordered Crist’s book, and for several days was talking about how big an impact this article had. I didn’t think at the time think that it was a breadcrumb of what I’m to do in 2021 going forward.

I now ask myself, “What kind of scaffolding in writing and image could possibly help us all face this ‘problem’ of the sixth extinction?” I put “problem” in quotes to signify that the real problem isn’t the biological problem of a die-off of 50% of the world’s species in this century, as hard as that will be to cope with. The “problem” is that the vast majority of people on this planet, at least in the Western world, don’t have the perceptual or thinking tools, or motivation to even imagine a different way of living that is actually ecologically sustainable. This lack could accelerate the extinction as a result, and for sure ensure that anger and mistrust will accompany the change. Crist argues that what we don’t have this time is time. It’s happening now.

I’m not sure yet what I can do personally. Will I be part of the acceleration?

Taking a Stand

I notice as I write that I keep thinking about Gretta Thunberg, the young Swedish girl who has ignited a youth revolution in response to the climate crisis. Did she know what she was doing? I don’t think so. She simply had the courage to speak her feelings and do so in a public forum, and open to a movement, a collaboration that would far transcend her.

If she can, why can’t I? Why can’t we? I don’t believe that knowing how to respond to the sixth extinction is required to stand up to it, and in it, with full awareness and readiness to ask fundamental questions and learn what we need to learn to change, any more than I knew what standing in front of the beast on Mt. Shasta would mean. I do know that context matters, and as complexity theorists have discovered, a small change in the context of a dynamic system can affect huge change.

So, I begin my new year sharing this dream. We are in a time of enormous turbulence. Will we be ones who stand up? Can we actually feel this happening with as much depth as we are feeling the losses from the pandemic?

I hope my sharing strikes a responsive chord. I intend to explore these ideas further through our Global Learning & Exchange Network. You are invited to join our inquiry there if you like. I and many committed colleagues will be there.

I don’t need to describe my full process here but can easily remember how powerful it felt. Building it took many hours. So did disassembling it. It was easily 8 feet long. What deeply disturbed me was my grasping experientially the extent of the systemically embedded exploitation mindset. But more disturbing was trying to imagine what could stand up to it—represented by the little wand with a feather. After hours of circling and meditating and just sitting and writing about this experience, I ended up writing some of my core values on the wand—things like the golden rule, my Bodhicitta vow to serve the awakening of all sentient beings, and staying tuned to the light, and the source of vitality I find in embracing and respecting all life. But I hardly felt resolved about this.

I don’t need to describe my full process here but can easily remember how powerful it felt. Building it took many hours. So did disassembling it. It was easily 8 feet long. What deeply disturbed me was my grasping experientially the extent of the systemically embedded exploitation mindset. But more disturbing was trying to imagine what could stand up to it—represented by the little wand with a feather. After hours of circling and meditating and just sitting and writing about this experience, I ended up writing some of my core values on the wand—things like the golden rule, my Bodhicitta vow to serve the awakening of all sentient beings, and staying tuned to the light, and the source of vitality I find in embracing and respecting all life. But I hardly felt resolved about this.

The Story of the Resurrection

The Story of the Resurrection