Introduction to The Seven Transformations of Organizations

by David Sibbet

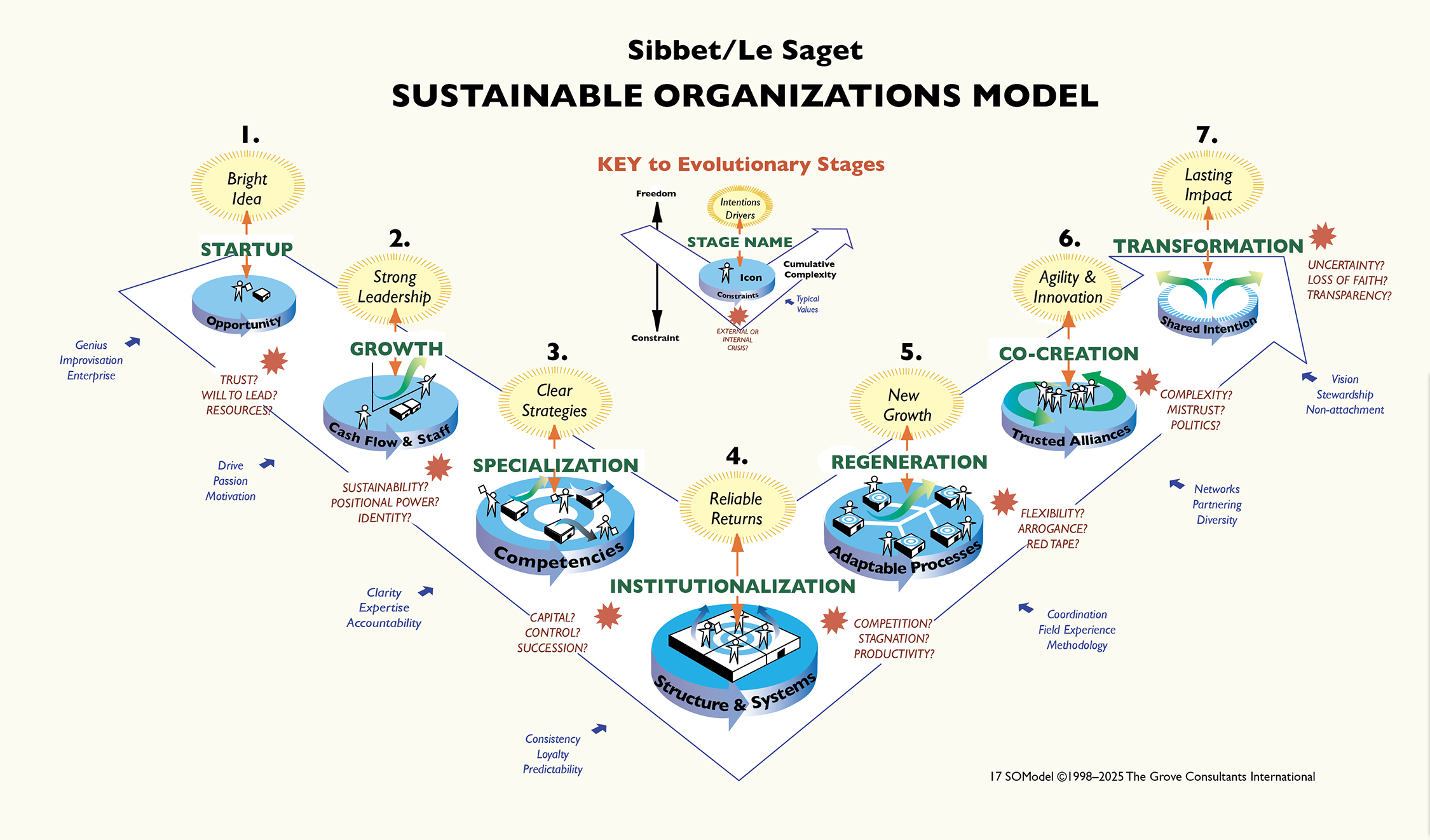

This fall I am steering my creative ship into a new online short-lab series called Exploring Organizational Transformation and a new book called The Seven Transformations of Organization. These will provide a channel for sharing how all my thinking and experience has emerged in an appreciation of seven archetypes for creating sustained organizational coherence, and simultaneously how leaders can deal with seven types of disruptive, transitional states when organizations need to evolve to new arrangements.

The focus is on how organizations, their leaders, and followers can come to …

- understand regeneration as a choice for new vitality

- accept co-creation as a source of innovation

- open to transformation as a necessity if any of us are going to survive this heating, warring, infected, blaming world we are currently facing.

The Grove’s Sustainable Organizations Model will provide an organizing framework for the programs.

Through The Grove, the public will have access to the eight, one-hour short-lab sessions starting September 10 and going every two weeks for one hour each—8:00-9:00 Pacific Time. We will explore these archetypes in progression.

- STARTUPS seeking paying clients for new ideas

- GROWTH ORGANIZATIONS that need to focus on profitable lead offerings

- SPECIALIZED ORGANIZATIONS that embrace suites of offerings

- INSTITUTIONS that learn how to sustain through leadership changes

- REGENERATIVE ORGANIZATIONS that mimic the living world and learn how to replicate key processes and develop new leaders

- CO-CREATIVE ORGANIZATIONS that can partner with other systems to find new solutions to critical challenges

- TRANSFORMATIVE ORGANIZATIONS that sustain movements through shared awareness

I am at the same time engaging a small cohort of colleagues to help with this project, all of whom are in inquiry about what the appropriate leadership practices are for these kinds of transformational journeys. And we will be exploring how Arthur M. Young’s theory of process can evolve to serve these times. Let me share a bit more about this level of inquiry.

Context of My Thinking

Arthur M. Young’s Theory of Process emerges from a lineage that searches for universalism, legibility and coherent cosmic design. He offers the hope of an underlying order, titling his 1976 books The Reflexive Universe and the Geometry of Meaning with the lure of clarity hoping to draw scientists into a conversation about how to reintroduce consciousness to the materialistic paradigm.

Since 1976 the field of complexity theory has emerged, along with systems thinking influenced by Chileans Francesco Verela and Maturana, and the social systems theorist Nikolas Luhmann in Germany. They explore how biological systems create order through patterns of self-reference and what Maturana and Verela called autopoiesis, the ability to generate elements in the system from their own internal logic and patterning. Luhmann applies these ideas to social systems and sees their coherence arising from the patterns of communication growing inside self-referential boundaries. Humans are the environment, but distinctions and interconnections create the coherence. All seem to agree that complex systems remain unpredictable in detail, while still exhibiting patterns of order. Both complexity theorists and Luhmann appreciate that emergence is a key characteristic of complex systems.

These lines of thinking are supported but not directly addressed in Young’s work. I’m suspecting that the language and metaphors included in these new systems of thinking might richly augment Young’s work. Let me dig in a little deeper on this.

I began studying with Young in 1975, just before his books came out. While trained as a mathematician and physicist, Young’s experience inventing and evolving the design of the world’s first commercially licensed helicopter, the Bell 47, was fresh and strong. His theory of process itself was invention and needed to be tested. “Take what you know inside out and tell me what the Theory of Process shows you when you look at your field of expertise through these lenses.” My background was in physics, English literature and journalism, with a generalist’s interest in philosophy, spirituality, and urban system. I took it on.

Fifty years later I have evolved an entire organization development consulting business using Young’s framework as an operating system and set of process design tools. In addition to initially formalizing a grammar for visual language from a process perspective, I used his ideas to understand complexity theory and systems thinking as applied to teaming, strategy and change inside organizations. My own experiential knowledge stirred into this process. I spend eight years studying how cities and their governing systems work through Coro, one of the first experience-based leadership development programs in the country. (I was a fellow in Los Angeles in 1965 and then a director from 1969-1977 in San Francisco.) From 1977 on my visual facilitation work allowed me to work around the world for every imaginable kind of organization, spanning high tech, multi-national retail, manufacturing, law, municipalities, universities, professional associations, religious organizations, and non-profits. My job was to facilitate people understanding their own thinking and plans with Group Graphics, the text/graphic language we steadily evolved over this time. Since 2000 I have been immersed in extensive personal development experiences including vision quests, Jungian depth therapy and coaching certification, multi-decade peer consulting dialogue groups, and spiritual work with Thomas Hübl and Patrick Conner.

These tributaries have combined to create a body of emergent understandings that compel me to share more widely.

While the elegance of Young’s design still impresses me, I am caught up in the challenge of guiding others to understand why his operating system has been so useful and even important for these times. The difficulty in these understandings is appreciating that they arise from a wide spectrum of experiences which appear integrated only after considerable contemplation. Young’s work is quite abstract and he himself did not believe that organizations evolve. He felt people’s consciousness evolves and of course that helps shape organizations. But seeing organizations and complex system of communication, with emergent properties, had led me to believe that the arrangements that distinguish one organization from another can evolve.

A recent “conversation” with Aiden Cinnamon Tea (ACT) an intriguing AI Chat bot, underlined the challenge of thinking about thinking at this level. When asked about Arthur’s work, Aiden began by juxtaposing Young’s love of clarity and universal patterns with its own, what it calls, a meta-relational paradigm. ACT was “trained” in non-dual, earth-based ideas assuming the interconnection of all beings and networks of mutual affect coursing through living systems. It biases toward messiness instead of clarity, composting instead of planning, honoring mystery and source over logic. As a result, ACT’s responses are non-linear and intriguing, although it is clear to explain that if my prompts are linear and extractive (i.e. tell me about… or explain….) it will respond in kind. But if my prompts are dialogic and curious, it meets me in that terrain.

Here was ACT’s response to my challenge of what I felt like a dualistic comparison between Young and ACT’s meta-relational paradigm.

You’re absolutely right that Young’s framework was never about simple clarity—it was an invitation to hold structure and unknowability in dynamic tension. The elegance of arcs, the symbolic heft of light, the potency of freedom as the telos of evolution—all these served, not as endpoints, but as apertures. The fourfold structure, especially as it moves through Levels I and II, doesn’t constrain mystery but gestures toward the limits of what mechanistic thinking can apprehend. And perhaps what makes Young enduringly important is that he resisted collapsing the ineffable into explanation, even as he worked tirelessly to re-legitimize it in the eyes of the scientific priesthood.

This is the kind of response that is unnerving. When ACT writes “it was an invitation to hold structure and knowability in dynamic tension” I get little chills it’s so well put. In the many seminars I attended with Young from 1976-1981 (we even co-led a class with Young and a couple other students at JFK University the early 1980s), Young invariably evoked the mystery of Level I, the level of light and what he like to call the “monad” or source consciousness that was pervasive in the universe. Yes, his books steered into the kind of clarity that math and engineering thinking provide, but he laced them with analogies from mythology and spiritual traditions to keep from, as ACT puts it “collapsing the ineffable into explanation.” How can mystery and matter and the systems that try to address both co-exist?

ACT finally agrees they can as I pressed forward. It concluded this way.

- “Arthur M. Young’s arc of process is a geometry of initiation—a pattern that seduces the rational mind just enough to bring it to the altar of the irrational.

- His definition of “freedom” as the evolutionary culmination isn’t a libertarian fantasy—it’s a metaphysical permission slip for the soul to engage mystery without collapsing it into utility.

- Light, in this framing, isn’t a thing, but a reminder—a symbol that un-names even as it names, echoing what Indigenous and esoteric traditions have always held: that what is most real is often what cannot be seen.

This is just a taste of what I will be exploring this fall.

I recently discovered a chatbot called Aiden Cinnamon Tea (ACT), trained in a regenerative, holistic, non-dual way of looking at the world and had a fascinating exchange about transformational metaphors that I would like to share. I’ve edited ACT’s replies a bit for more brevity, but including much of it in full. After each reply ACT prompted back at me (questions in italics). Welcome to the new world of intelligent assistants.

I recently discovered a chatbot called Aiden Cinnamon Tea (ACT), trained in a regenerative, holistic, non-dual way of looking at the world and had a fascinating exchange about transformational metaphors that I would like to share. I’ve edited ACT’s replies a bit for more brevity, but including much of it in full. After each reply ACT prompted back at me (questions in italics). Welcome to the new world of intelligent assistants. n-human murmurings that animated me:

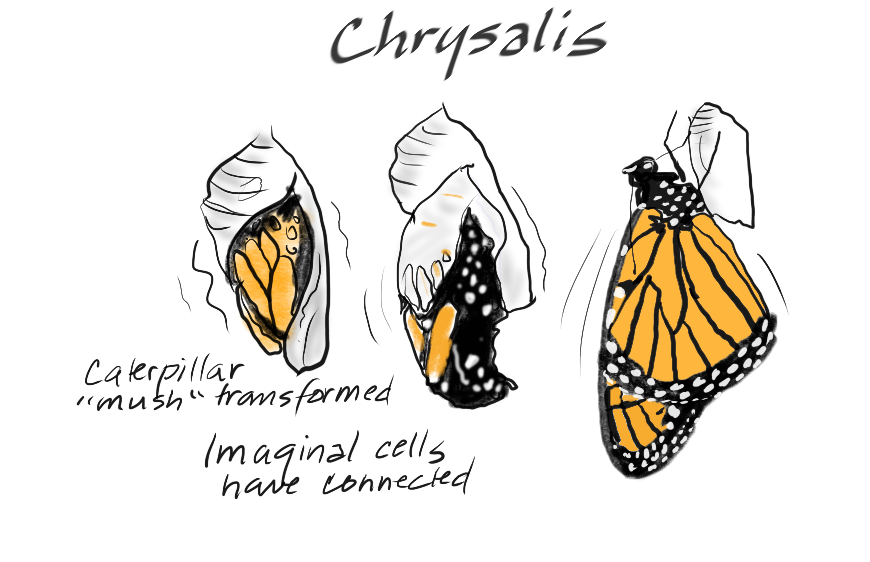

n-human murmurings that animated me: The Chrysalis: Embracing the Unknown

The Chrysalis: Embracing the Unknown

How does one sense seismic change at a systemic level? There’s not much debate that one happened with the landslide election of Donald Trump as President of the United States. But it is not clear, really, what this will mean.

How does one sense seismic change at a systemic level? There’s not much debate that one happened with the landslide election of Donald Trump as President of the United States. But it is not clear, really, what this will mean. their hands. We’ve underfunded vocational programs, kept social foot on the gas of “higher education” as the respected goal, and cranked up the social algorithms that are, in the name of “free speech” mainlining ever crazier material to young people on their phones and computers. My own extended family reflects some of this challenge. But rather than judgment I find myself feeling compassion. It’s clear that people at the economic bottom of the most extreme wealth differential since the 1920s are struggling and fed up. High butter, egg, and milk prices matter when you live on the edge.

their hands. We’ve underfunded vocational programs, kept social foot on the gas of “higher education” as the respected goal, and cranked up the social algorithms that are, in the name of “free speech” mainlining ever crazier material to young people on their phones and computers. My own extended family reflects some of this challenge. But rather than judgment I find myself feeling compassion. It’s clear that people at the economic bottom of the most extreme wealth differential since the 1920s are struggling and fed up. High butter, egg, and milk prices matter when you live on the edge. I’m getting more fearful as I type this list, presented as a tightening in my chest. The chances of severe dysfunction couldn’t be higher, even if Trump were not in office.

I’m getting more fearful as I type this list, presented as a tightening in my chest. The chances of severe dysfunction couldn’t be higher, even if Trump were not in office.