Stroke of Insight

Sometimes guidance just appears. No warning. It happened to me at the end of a three-day Leadership Transformation Workshop in Minnesota, in the last five minutes on a Friday to be precise. I got up to go to the table in back where I had my journal and almost fell over. My left leg felt like it had gone completely asleep. I was helped back, sat, and realized it wasn’t asleep. It just wasn’t connected any more. I had had a stroke!

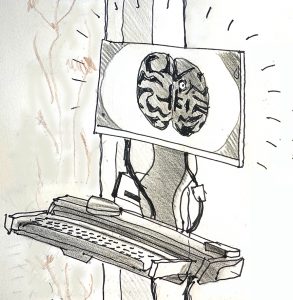

Thirty minutes later after a drive to a nearby emergency room I was in a CAT scan and found that I had a half inch long hemorrhagic bleed (stroke) on the surface of my right, central cortex, near my left side motor controls. I could feel the skin on my leg. I could move it with my big muscles, but I was not in control of it. Needless to say, I was on my back at 30 degrees angle the next two days, awakened every hour for a complete check on my cognition, eye movements, hands, leg lifts—all through the night.

Thirty minutes later after a drive to a nearby emergency room I was in a CAT scan and found that I had a half inch long hemorrhagic bleed (stroke) on the surface of my right, central cortex, near my left side motor controls. I could feel the skin on my leg. I could move it with my big muscles, but I was not in control of it. Needless to say, I was on my back at 30 degrees angle the next two days, awakened every hour for a complete check on my cognition, eye movements, hands, leg lifts—all through the night.

I’m happy to say that this was a “small” stroke. I was released Sunday at noon and flew back to San Francisco, with referrals from the neurologists there and complete records. A second CAT Scan and an MRI did not detect anything else. No cancer. No clots. No aneurisms. No progression. And they saw I could make it around with a walker already, which they provided from my trip home.

They didn’t measure my psyche, of course. That is outside the purview of most modern medicine. Although staff at Health East’s University Hospital ICU, where I was sent, by ambulance, after the initial scan in ER, was uniformly comforting and caring, they were not “measuring” the larger impact. The therapist was more focused on the exercises I should do repeatedly. They did keep asking me my name, date of birth, and if I remembered why I was in the hospital.

I’ve lived my life gifted with immense curiosity and this experience has me fascinated. If I were massively crippled, I’d probably feel differently, but I just came in from a slow walk around my neighborhood two weeks later and am feeling pretty good. But my mind is whirling. What does it mean to have a stroke?

- I now know that merely saying this word shakes people up. It covers so much and is so common, that everyone has some connection. It is a big deal. Our staff at The Grove and my kids think it is a big deal. So does Gisela, my partner and wife. No flying or driving until I get cleared by the neurologist I meet with tomorrow. Everyone at the University Hospital said that this isn’t a repeating kind of thing, especially with a person with normal blood pressure and no hypertension.

- I also know that my body knows how to heal. My brother, John, who has practiced reflexology, muscle testing, and applied kinesiology for as long as I’ve been facilitating, came over and completely checked me out. He was amazed at my progress, aided by a lot by moving around like a Tai Chi practitioner. I figured my right leg knows how to move. Teach the left. Rock back and forth. John agreed and encouraged my movements. I also kept imagining I was in Avatar hooking up to one of the flying dragons. My leg’s nerve endings reaching up. My brain coming down. Both eventually reconnecting.

- I have discovered that there are many many tinier muscles that bring stability to a leg, and it isn’t so clear how to reconnect them. Why does my left leg seem to snap back instead of just bending back? I feel like I’m on some kind of plateau in recovery. The leg feels weaker, although I didn’t hurt it in any way. Maybe the neurologist at Kaiser, who I see for the first tomorrow, will have some ideas.

- I know that situations like this have cascading effects, and this is no exception. In my case my ability to hear high frequencies has been declining and is now gone. My hearing aids compensate, but not enough to hear the soft, mumbled words of a person with a high-pitched voice. In an echoey room or sketchy zoom connection I miss key words. This isn’t acceptable if your job is to record what people say visually (and accurately). The room in Minnesota was a real struggle in that regard. I’ve been concerned for a while, but it took the stroke for me to say “enough.” Gisela agreed it was truly time for me to stop facilitating meetings and that she and The Grove team could take over the remaining work on our books. Fortunately, since she has become CEO of The Grove the team is growing again and are managing beautifully. Our clients have been wonderfully accepting.

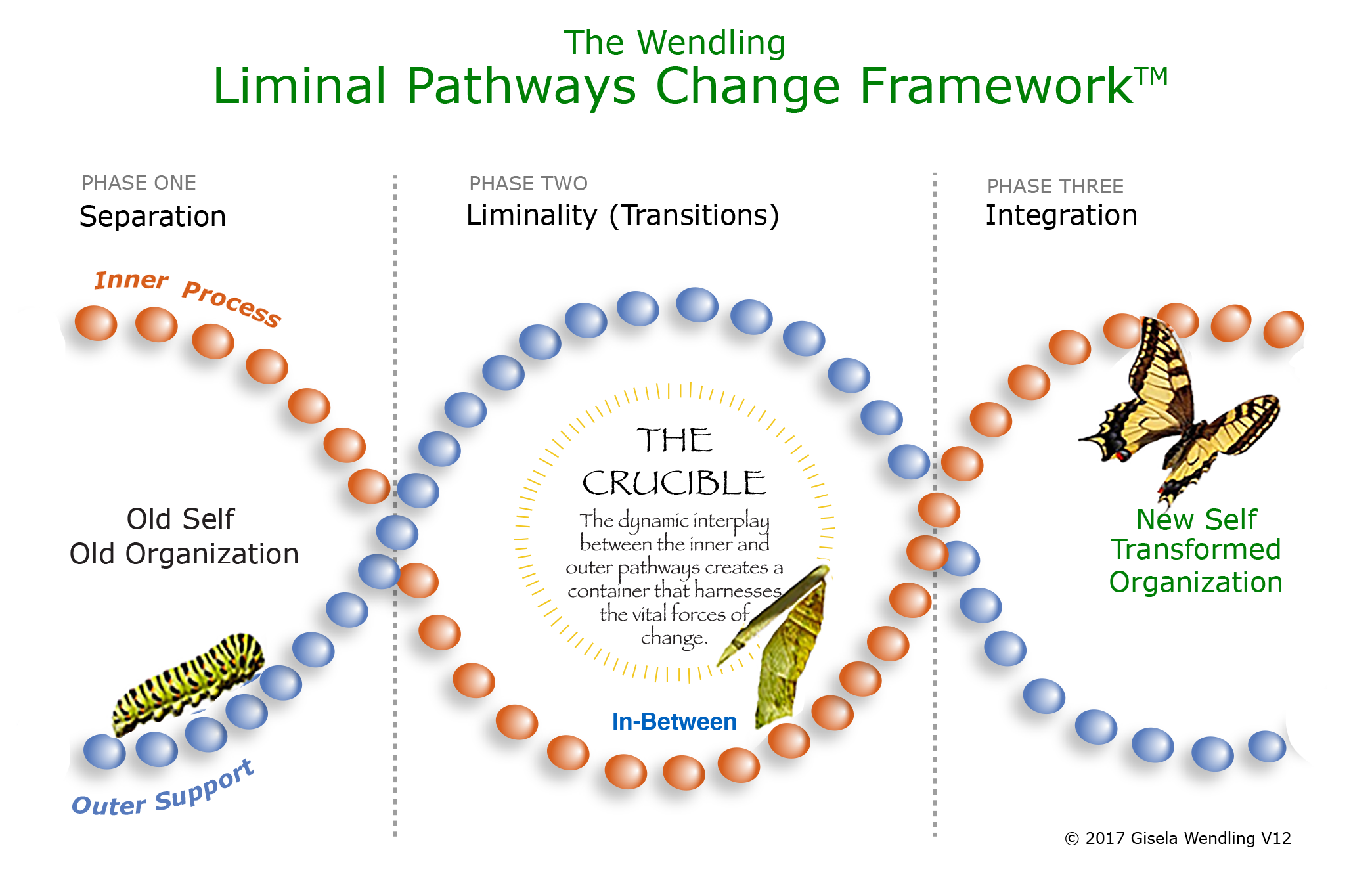

- So, I not only had a real physical stroke, small though it may be, I have retired from a kind of work that I’ve done for 52 years, if you count my doing the first Group Graphics workshop at Coro in 1972. That is like having a professional stroke. And I am now experiencing truly liminal space. The “recovery pattern” is not clear. All kinds of things are possible. For the first time in years and years I don’t have to carry the responsibility for payroll. I don’t have to schedule my life around big meetings. But my psyche is busy trying to re-establish itself just like my leg. “You could start a You Tube channel.” “You could write a new book (it’s already mostly written).” “You could work on that novel you discovered you wrote in 2006 (and wasn’t bad).” You could conduct Vision Labs at your own home.” “What about executive coaching?”

- The biggest insight is that I need to take some time to experience myself in a completely new way. I’m suspecting that much of my adult life I’ve been guided by programming that is very deep and has a lot to do with how that little baby back in Two Rock initially encountered the world, and what I thought would work to keep my parents in touch with me, and what was okay and not okay regarding being myself. Ooops. You mean I learned to repress things to please my parents? But what things? And was getting attention for being an amazing artist and craftsperson what I really wanted, or a substitute for something else, like nurturing love? It’s helped that during this recovery time I’ve had time to continue reading Gabor Mates’ The Myth of the Normal. (If you want to understand the stress of our times it is a must read.)

I’m posting this piece in my blog because I think those of you who really care about awareness and facilitation and helping people get through life would appreciate knowing what a colleague like me is going through at a true turning point. I suspect I will look back on this event and this time as a gift, even if it just appeared out of the blue.

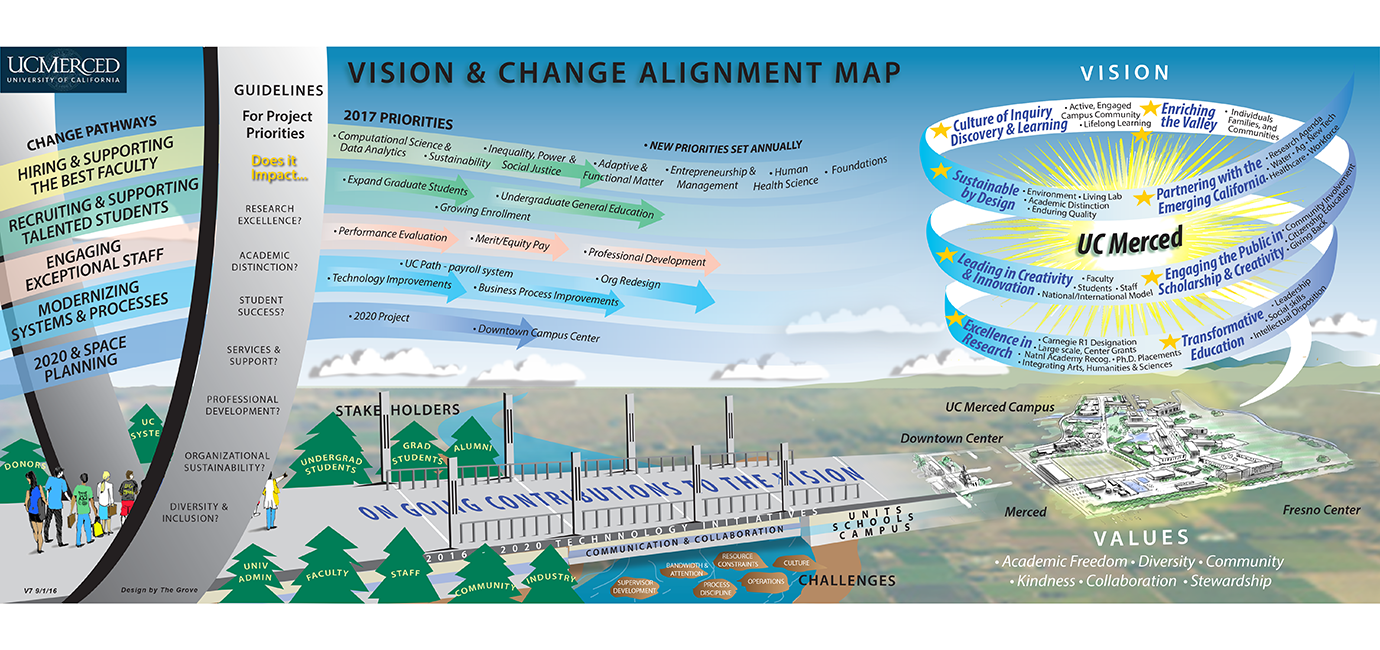

This September Gisela Wendling became CEO of The Grove Consultants International, the comp

This September Gisela Wendling became CEO of The Grove Consultants International, the comp any that I began in 1977 as Sibbet & Associates, and led through its incorporation as Graphic Guides, Inc. in 1988 and then the name change to The Grove in 1993. I want to share some reflections about our succession process, which is guiding me into the wonderful territory of life change.

any that I began in 1977 as Sibbet & Associates, and led through its incorporation as Graphic Guides, Inc. in 1988 and then the name change to The Grove in 1993. I want to share some reflections about our succession process, which is guiding me into the wonderful territory of life change.

Is Visualization Both Integrative and Disruptive?

Is Visualization Both Integrative and Disruptive? I’m doing more of this with colleagues. Recently two of my friends and GLEN colleagues, Alan Briskin, and Mary Gelinas, have been writing a book about Three Field Awareness. They are working to integrate research in the areas of personal, social, and noetic fields, and of course interleaving their own long practices. Mary is deeply engaged in somatic work, taking the language and deep patterns of our embodied knowing seriously. Alan has been studying collective wisdom for years. These matters defy easy representation. I have been working with them to see if there are some ways to visualize these concepts without falling into the trap of being inappropriately “clear.”

I’m doing more of this with colleagues. Recently two of my friends and GLEN colleagues, Alan Briskin, and Mary Gelinas, have been writing a book about Three Field Awareness. They are working to integrate research in the areas of personal, social, and noetic fields, and of course interleaving their own long practices. Mary is deeply engaged in somatic work, taking the language and deep patterns of our embodied knowing seriously. Alan has been studying collective wisdom for years. These matters defy easy representation. I have been working with them to see if there are some ways to visualize these concepts without falling into the trap of being inappropriately “clear.”