ELECTION REACTIONS—Spirit, Heart, Mind & Body

How does one sense seismic change at a systemic level? There’s not much debate that one happened with the landslide election of Donald Trump as President of the United States. But it is not clear, really, what this will mean.

How does one sense seismic change at a systemic level? There’s not much debate that one happened with the landslide election of Donald Trump as President of the United States. But it is not clear, really, what this will mean.

I entertain the idea that each of us is interconnected with the whole at a bio synergetic level, in that we, as humans, can sense energy fields and probably fields of consciousness. At some level I think all living entities can feel each other. But it is not easy to be conscious of these connections. However, these assumptions lead me to honor looking at my own reactions (spirit, heart, mind and body) for some sensing of the whole.

Relief

I’m surprised at how calm I feel with political messaging disappearing and the uncertainty of who will win settled. I was anticipating sustained political unrest whoever won, but this isn’t happening, right now. I don’t live on social media so I may not be aware of what is happening on the dark net. But I’m very relieved there is not blood in the streets. My nervous system seems to be quieting.

Rising Compassion

In my heart I keep thinking about young men and their bleak prospects, at least for the unentitled, the incel, the trans, the ones that want to work with their hands. We’ve underfunded vocational programs, kept social foot on the gas of “higher education” as the respected goal, and cranked up the social algorithms that are, in the name of “free speech” mainlining ever crazier material to young people on their phones and computers. My own extended family reflects some of this challenge. But rather than judgment I find myself feeling compassion. It’s clear that people at the economic bottom of the most extreme wealth differential since the 1920s are struggling and fed up. High butter, egg, and milk prices matter when you live on the edge.

their hands. We’ve underfunded vocational programs, kept social foot on the gas of “higher education” as the respected goal, and cranked up the social algorithms that are, in the name of “free speech” mainlining ever crazier material to young people on their phones and computers. My own extended family reflects some of this challenge. But rather than judgment I find myself feeling compassion. It’s clear that people at the economic bottom of the most extreme wealth differential since the 1920s are struggling and fed up. High butter, egg, and milk prices matter when you live on the edge.

Anger

I can barely watch, as a former journalist in the four-newspaper city of Chicago, what is now passing as journalism. It seems like a swirl of opinion and pundits on all channels. Benjamin Franklin created newspapers because he knew the colonies needed a sense of identity. Now local news sources are shrinking as rapidly as the ice flows in Greenland. And we are left with a national media clearly complicit in the attention economy’s appreciation that more catastrophic, violent and bizarre their reports the more people will watch. Disasters like the recent hurricane and floods don’t happen once—they loop the most jarring pictures days after day. I know from 2016 that CNN, who brought Donald Trump and the Apprentice to audiences, covered Trump 30% more than the other networks, purposely provoking and criticizing in what now seems like a political version of prime-time wrestling. Their bottom line turned black as a result. Everywhere I look people seem to be making money off the blame game and the escalating back-and-forth charges.

Fear

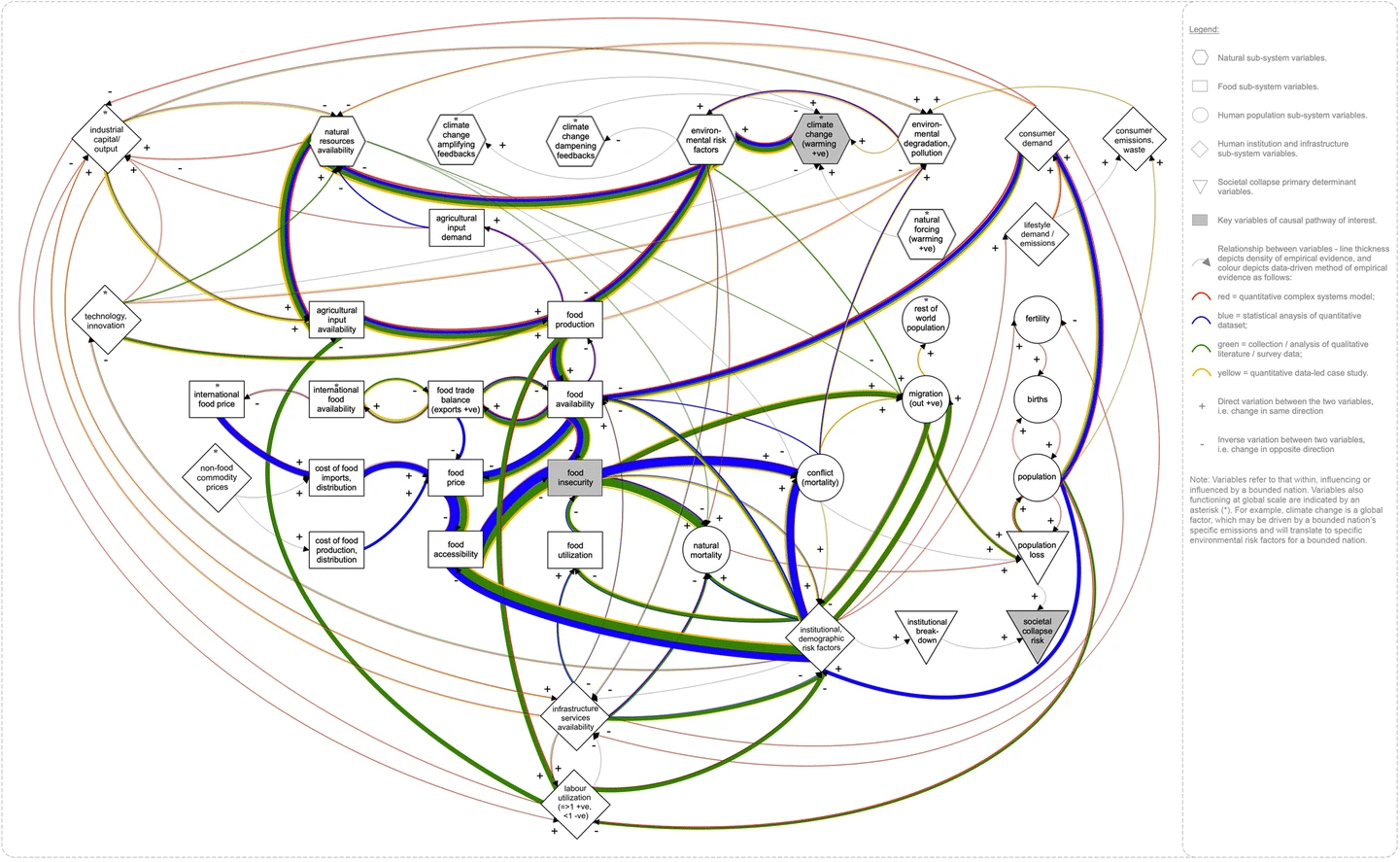

I’m a system’s thinker, after 45 years of organization consulting and visualizing the widest range of meeting and planning processes you can imagine. There are some things about systems that are well understood.

- They don’t change through tinkering and single solutions.

- There are always unintended consequences.

- The system called the “Ecosystem” is undergoing massive destabilization due to global warming that will destabilize many of its subsystems.

- Growing trusted systems is much hard than disrupting them.

- A tightly interconnected system is easier to destabilize than a more loosely coupled one (this is why nature is more resilient than large corporations).

- Systems do not present themselves so you can see, touch, and feel them like an object. Understanding one requires pulling together many perspectives and representations and long study. This is why research takes so long.

- Feedback loops help regulate systems, but if the feedback is not received and decisions adjusted, feedback’s stabilizing influence can result in overshoot and collapse.

This causal loop diagram of climate change, food insecurity, and social collapse provides a dramatic, graphic reflection of how difficult it is to understand (and stabilize) systems. (It is from SpringerNature).

I’m getting more fearful as I type this list, presented as a tightening in my chest. The chances of severe dysfunction couldn’t be higher, even if Trump were not in office.

I’m getting more fearful as I type this list, presented as a tightening in my chest. The chances of severe dysfunction couldn’t be higher, even if Trump were not in office.

Politics is Perception

I learned this through eight years of running Coro’s Fellowships in Public Affairs in the SF Bay Area. I lived through the time when TV became a factor during the rise of Diane Feinstein and meetings transformed from discourse to sound bite generators. People can’t really understand the systemic implications of decisions and policies right away, so spin substitutes for fact and analysis. We are in a time of myth making amplified by technologies we’ve never experienced operating at such a massive, manipulative level. And AI is just getting started in this game. Just as finance has been taken over by the financial computer jockey’s in the financial hubs, perception will be owned by the ones with the most ubiquitous and advance technologies. No wonder Elon Musk and the tech billionaires want to be in on politics. Their systems ARE the politics now.

Community

I believe that with system destabilization real, geographic communities will become more important again. We’ve need to know food and water sources more directly. We’ll need to know who can do what. We’ll need each other for support. This may be true of organizations that think they can sustain themselves virtually without real relationships as the continuity and “glue.” In the last week I’ve thought more about my own town of Petaluma than ever before.

Realizing Visionary Futures

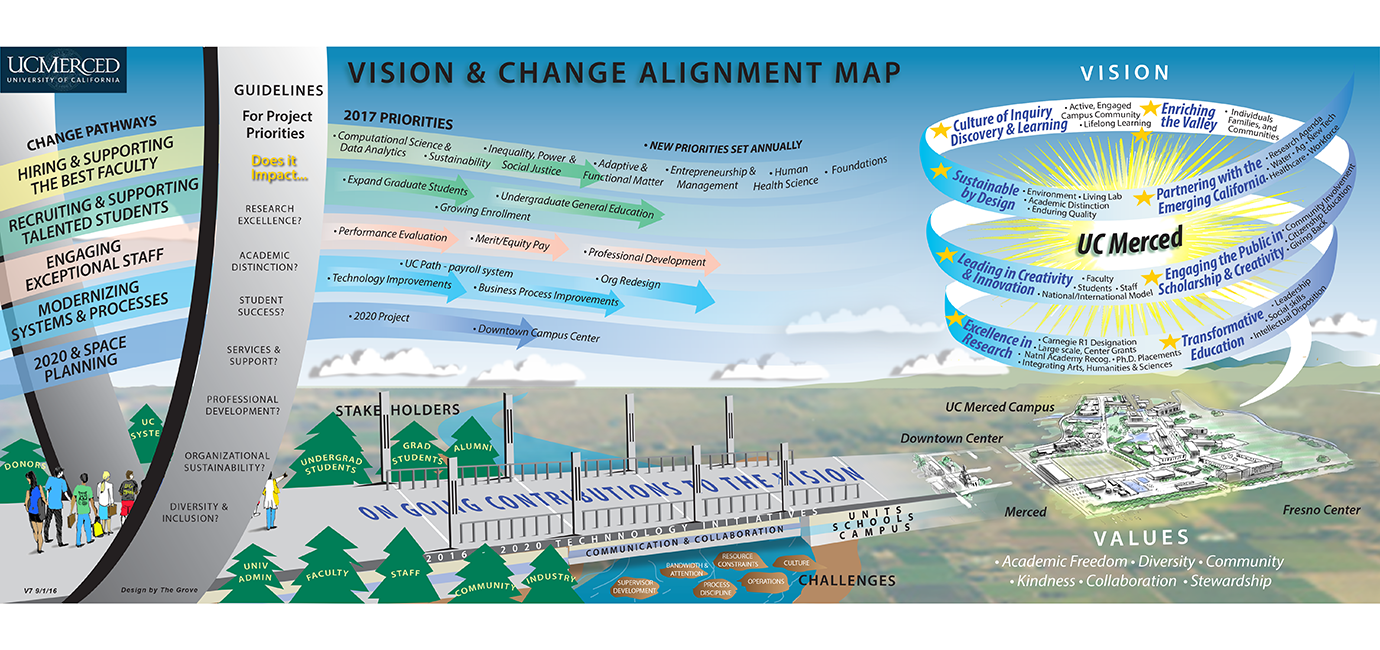

I’m emerging from the election time even more committed to The Groves purpose of helping people and organizations realize their visions. The skills of collaboration, facilitation, and leading social change could not be more important.

Inner Stability

A concluding thought: If I can’t find coherence in my outer world very easily, I believe I can work on staying grounded in my inner world and my relational world. I can choose to be inspired by the example of Buddha, Christ, and people like Thich Nhat Hanh, who remained lovingly oriented all through the Vietnam War. I can choose to see my urge to blame and “other” people as my own experiences in not being accepted playing out in my projections. I believe that most people respond to love and respect, and that my ability to be that way starts with loving and respecting my own self, and the flow of my own soul’s journey.

I also believe that I can call on the land and nature itself to support me, even as my body slowly declines with age. I grew up in the mountains, and they remain magnificent, despite everything!

It has felt good writing all this. We are in this together As we say in our circles, I have spoken.

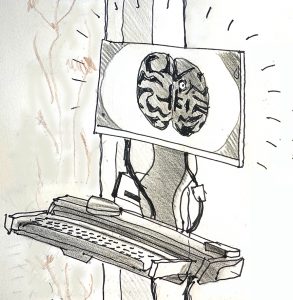

Thirty minutes later after a drive to a nearby emergency room I was in a CAT scan and found that I had a half inch long hemorrhagic bleed (stroke) on the surface of my right, central cortex, near my left side motor controls. I could feel the skin on my leg. I could move it with my big muscles, but I was not in control of it. Needless to say, I was on my back at 30 degrees angle the next two days, awakened every hour for a complete check on my cognition, eye movements, hands, leg lifts—all through the night.

Thirty minutes later after a drive to a nearby emergency room I was in a CAT scan and found that I had a half inch long hemorrhagic bleed (stroke) on the surface of my right, central cortex, near my left side motor controls. I could feel the skin on my leg. I could move it with my big muscles, but I was not in control of it. Needless to say, I was on my back at 30 degrees angle the next two days, awakened every hour for a complete check on my cognition, eye movements, hands, leg lifts—all through the night. This September Gisela Wendling became CEO of The Grove Consultants International, the comp

This September Gisela Wendling became CEO of The Grove Consultants International, the comp any that I began in 1977 as Sibbet & Associates, and led through its incorporation as Graphic Guides, Inc. in 1988 and then the name change to The Grove in 1993. I want to share some reflections about our succession process, which is guiding me into the wonderful territory of life change.

any that I began in 1977 as Sibbet & Associates, and led through its incorporation as Graphic Guides, Inc. in 1988 and then the name change to The Grove in 1993. I want to share some reflections about our succession process, which is guiding me into the wonderful territory of life change.