Succession as a Gift of Emergence

This September Gisela Wendling became CEO of The Grove Consultants International, the comp

This September Gisela Wendling became CEO of The Grove Consultants International, the comp any that I began in 1977 as Sibbet & Associates, and led through its incorporation as Graphic Guides, Inc. in 1988 and then the name change to The Grove in 1993. I want to share some reflections about our succession process, which is guiding me into the wonderful territory of life change.

any that I began in 1977 as Sibbet & Associates, and led through its incorporation as Graphic Guides, Inc. in 1988 and then the name change to The Grove in 1993. I want to share some reflections about our succession process, which is guiding me into the wonderful territory of life change.

Some Context

The Grove Consultants International, as many of you know, was early in the business of visual facilitation. We called the method Group Graphics® and found that strategy consultants who wanted to differentiate loved the process and propelled our work at Apple, General Mills, Federal Industries in Canada, General Electric, and Bongrain. Because no other consultants were working this way, we could use our methods as a calling card. People remembered us whenever we facilitated meetings.

We added a teaming practice in the 1980’s after Alan Drexler and I co-developed the Drexler-Sibbet Team Performance ModelTM and its related survey. This has grown into its own business, with many tools, workshops, and licensees.

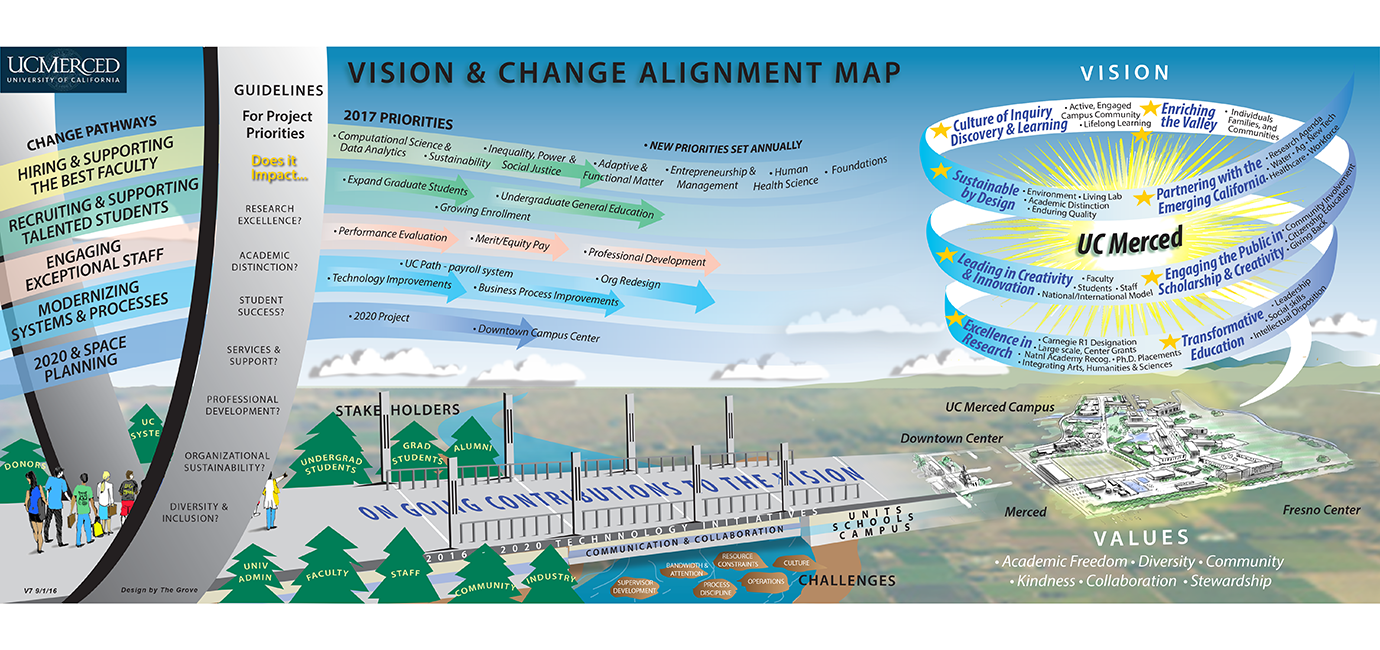

In the 1990’s The Grove grew rapidly with large, multi-year engagements with National Semiconductor, Hewlett Packard, and Mars, Inc. We developed large-scale Storymapping, and in the mid-nineties, Ed Claassen as our COO collaborated with me and the team to develop the Grove’s Strategic Visioning (SV) process and Graphic Guides.® These are the large graphic wall templates which are now ubiquitous. Again, we were one of the first to popularize this way of working. We conducted SV processes all over Silicon Valley as the Internet gained speed. We moved to our Presidio offices in 1998.

Visualization, teaming, and strategy guided us during the rocky 2000’s. The .com crash, 9/11, and then the great recession in 2009 impacted our company and the scale of projects clients would consider. But all three of our service areas continued to deliver results. After 2009 we moved to re-emphasize our origins as the Visual Meetings Company.

But life intervened. In 2013 my wife Susan died of cancer, after 46 years of marriage. Laurie Durnell and Bobby Pardini took over co-leadership of the company as I dealt with this enormous change. I was supported by my close friend Rob Eskridge, my counsellor Chayim Barton, and a dear colleague Gisela Wendling. Gisela’s life-long interest in change and Rites of Passages allowed her to help me hold Susan’s passing as a potential transformation. And it was. To our surprise, we fell in love and were married in 2016.

In 2014 Gisela joined The Grove as VP for Global Learning and senior consultant and we co-developed our Designing and Leading Change program to bring forward her work and take the Grove’s work to a new level. We also began the non-profit Global Learning & Development Network, or GLEN. While we could not have anticipated the pandemic, our focus on change and working virtually allowed us to pivot quickly to on-line workshops and direct help for our struggling client leaders. We could also see their organizations coping with the increasing impacts of climate change, economic ambiguity, climate migration, wealth gaps, political polarization, and many other challenges. Change was in the air.

Succession

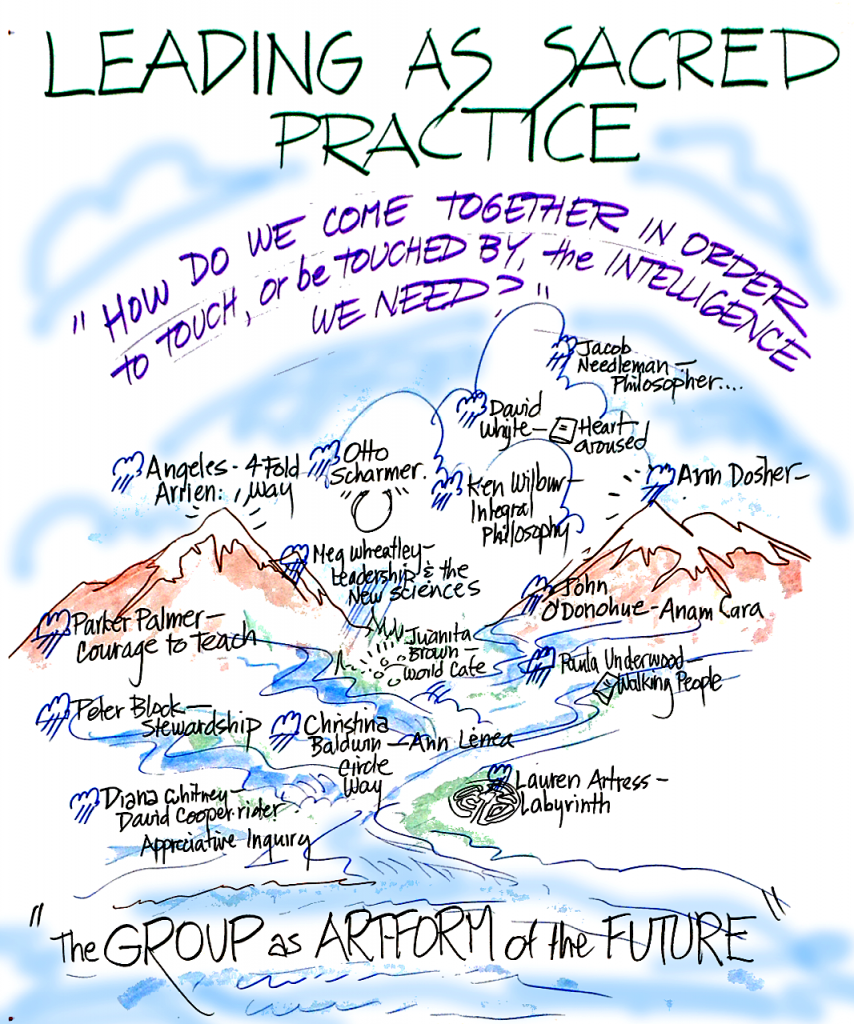

Having Gisela at The Grove transformed our work and renewed my interest in consulting. She led a master’s program in organization development at Sonoma State after receiving her doctoral in human and organization systems and development. We co-authored Visual Consulting: Designing & Leading Change with Wiley after a successful Visioning and Change Alignment process at UC Merced. The integration of dialogue, visual practice, change management and use of self, began to define a new approach.

This fall Gisela decided after a week-long silent retreat in Holland and a short vacation in Belgium, to step up to the role of CEO and lead The Grove into a new era. Her passion is to help leaders and their teams “Realize Visionary Futures.” Her becoming CEO is coincident with the publishing of her new book, The Liminal Pathways Study. We collaborated on the design and illustrations, but the creative vision was hers and I followed!

Living the Liminal Pathway

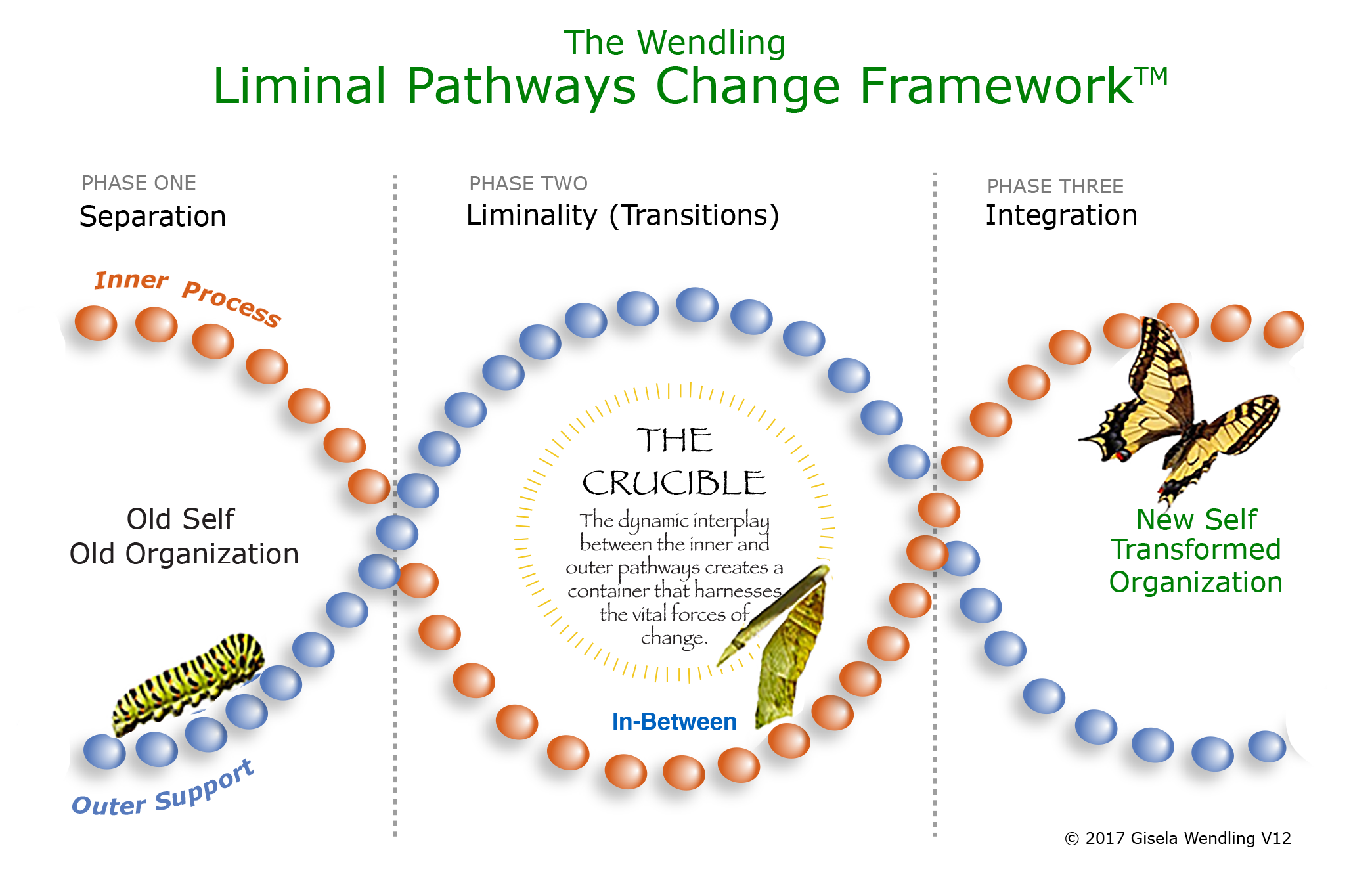

Gisela’s Liminal Pathways Change Framework (LPF) re-envisions the archetypal three-phased process of Rites of Passage as identified by the French anthropologist Arnold Van Gennep. Phase one is Separating. Phase two is the Liminal or “In-Between” phase. Phase three is Integration. Gisela’s framework highlights the inner and outer dynamics at play in each phase and the sequence of turning points that occur over the arc of a complete process. It is this process that is now unfolding for me.

I have let go of the formal position I held. I must also let go of large meeting graphic facilitation, involving our growing network of associates who are good at this. A year and a half ago, we let go of the Presidio offices, which we hadn’t used for three years during the pandemic to move into the warehouse where Grove Tools, Inc. run by Thom Sibbet as President, had a spacious upstairs office.

Entering Liminal Space

I am now deep in liminal space. I want my next moves to come from my deeper self. Already new rivers of interest are arising and flowing together but I am resisting being rushed. I asked for a vision this summer on my vision quest on Mt. Shasta and the takeaway was “constancy.” This is a different calling.

It is clear that I will be focused this next year in support as The Grove team responds to a new leader. Gisela is deeply appreciative of our historic ways of working and is visually very astute. The change work is proving to be an integrating approach. But the complexity of the post-Covid hybrid world is considerable and finding the best responses is challenging. Leaders of change need support as do their teams. I believe with Gisela’s leadership we can provide it.

At the same time, I’m fascinated with the way this liminal time is affecting me. I find myself feeling vulnerable, the way I did early in my career. I am also feeling full of all the capabilities that have developed over the 52 years of work all around the globe. In my field I would be considered an “expert” at process design and visual facilitation. But more and more I feel that my ability to connect broadly across many disciplines, organizations, and cultures may be more important than knowing how to use visualization. I’m asking myself, “What is the role of an elder?”

Working with The Light

Years ago, a workshop by Michael Meade provided a seed of insight that has been growing in my liminal space. Being an elder, he said, is the process of making a shrine to the spirit as the body falls away. And it is the blooming of my spirit that has my attention these days.

Another teacher, Dr. Niek Brouw, a Dutch somatic practitioner I and colleagues worked with in the late 1990s, defined spirit as our ability to handle light. It is reflected in our spine, the neurofibril optic trunk line that holds our bodies in coherence and connection. The idea of working with light itself has my attention. It is the work that our teacher Thomas Hübl invites.

This month Netflix brought out a short mini-series on Anthony Doerr’s amazing book, The Light We Cannot See, a story about Marie-Laure LeBlanc, a blind French girl at the end of the war who intersects with a young German soldier in the French town of Saint-Malo as American troops freed France from the Nazis. The light within is as vast as the light in the world, he writes, and this young woman, is connected this way. It guides her in incredible acts of bravery broadcasting coded coordinates through readings of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea that were instrumental in final days of the war.

I find myself moved by this story, and the need for using my inner light to guide me in this next phase, and for The Grove’s inner light to grow stronger as we move to support leaders who are daring to bring about visionary changes. I have a growing feeling that the confusion and incoherence of our times cannot be met just with logic and neatly arranged symbols on paper but needs the connection of people who share a vision of a world where people respect each other across differences and, and in Gisela’s words, are “empowered to be free and have choices.”

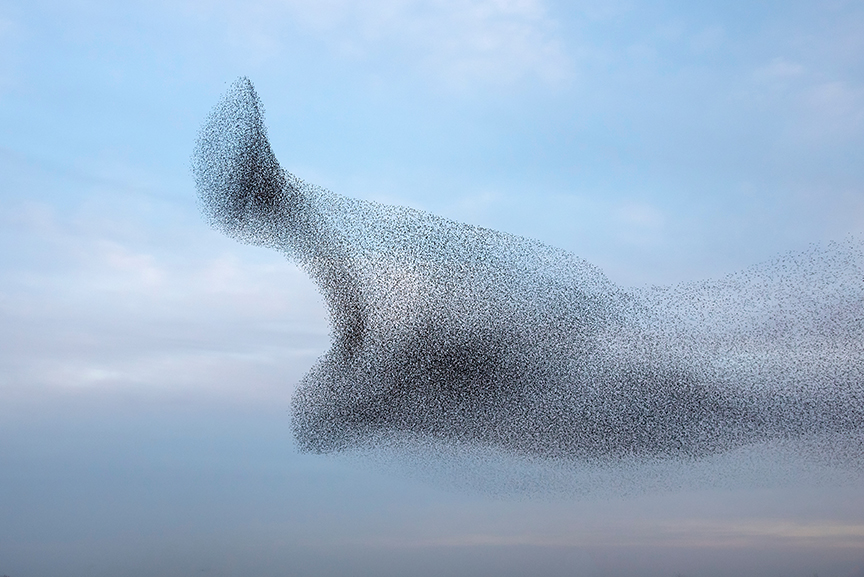

As I wait for my new direction to emerge, I stand by to respond to those who are responding to our broadcasts, who believe that authoritarianism and overcontrol is not a solution. I am recasting my understandings of graphic facilitation as a chance to embody differences and hold space for movement, evolution of the practice, and emergent insight. I’m wondering if returning to the origins of this work and teaching our new understandings might again transform the field.

My mentor Michael Doyle, co-founder of Interaction Associates and one of those bringing facilitation to organizational work in the 1970s, said as I began The Grove. “You can compete and defend, or you can share and lead.” I’ve followed his advice and carry it with me to this next phase. Stay tuned.

Is Visualization Both Integrative and Disruptive?

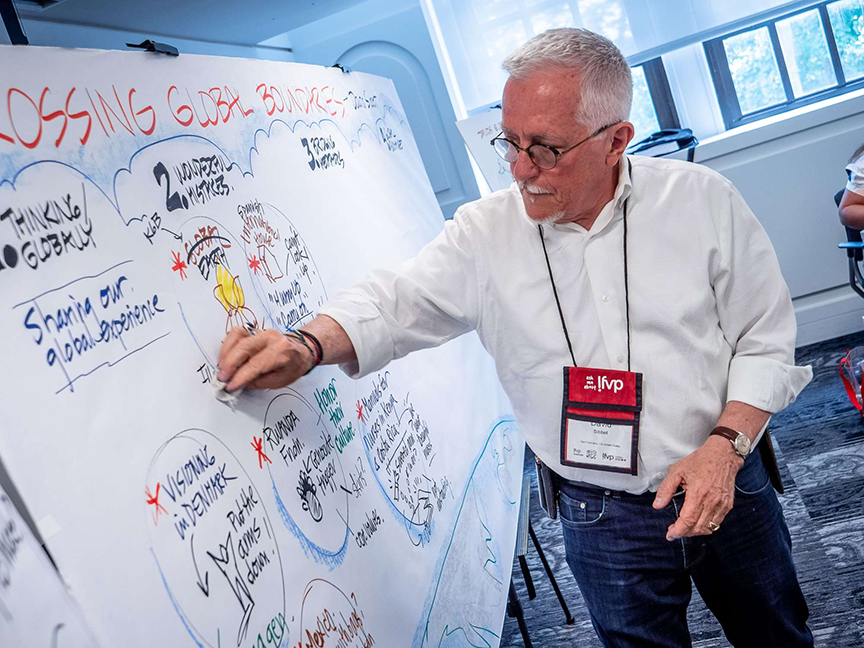

Is Visualization Both Integrative and Disruptive? I’m doing more of this with colleagues. Recently two of my friends and GLEN colleagues, Alan Briskin, and Mary Gelinas, have been writing a book about Three Field Awareness. They are working to integrate research in the areas of personal, social, and noetic fields, and of course interleaving their own long practices. Mary is deeply engaged in somatic work, taking the language and deep patterns of our embodied knowing seriously. Alan has been studying collective wisdom for years. These matters defy easy representation. I have been working with them to see if there are some ways to visualize these concepts without falling into the trap of being inappropriately “clear.”

I’m doing more of this with colleagues. Recently two of my friends and GLEN colleagues, Alan Briskin, and Mary Gelinas, have been writing a book about Three Field Awareness. They are working to integrate research in the areas of personal, social, and noetic fields, and of course interleaving their own long practices. Mary is deeply engaged in somatic work, taking the language and deep patterns of our embodied knowing seriously. Alan has been studying collective wisdom for years. These matters defy easy representation. I have been working with them to see if there are some ways to visualize these concepts without falling into the trap of being inappropriately “clear.”