Jun 18, 2019

Jun 18, 2019h

in

Cognition & Communications,

Community Building,

Contribution to the Field,

Global Learning,

Inspiration,

Leading Change,

Mental Models,

Organization Development,

Personal Development,

Process Theory,

Social Change,

Systems Theory,

Visualizing

by David Sibbet

A recent communication from the Organizational Development Network that outlined a definition of the field and its core values led me to think about the evolution of my own thinking about the field. I’m writing here to  share this reflection, and to share my hope for the future of the field. I’m not writing a history of OD, but of the quilt of understanding that provides me with direction as a process consultant, and might be useful to other practitioners who work in or with organizations.

share this reflection, and to share my hope for the future of the field. I’m not writing a history of OD, but of the quilt of understanding that provides me with direction as a process consultant, and might be useful to other practitioners who work in or with organizations.

Context

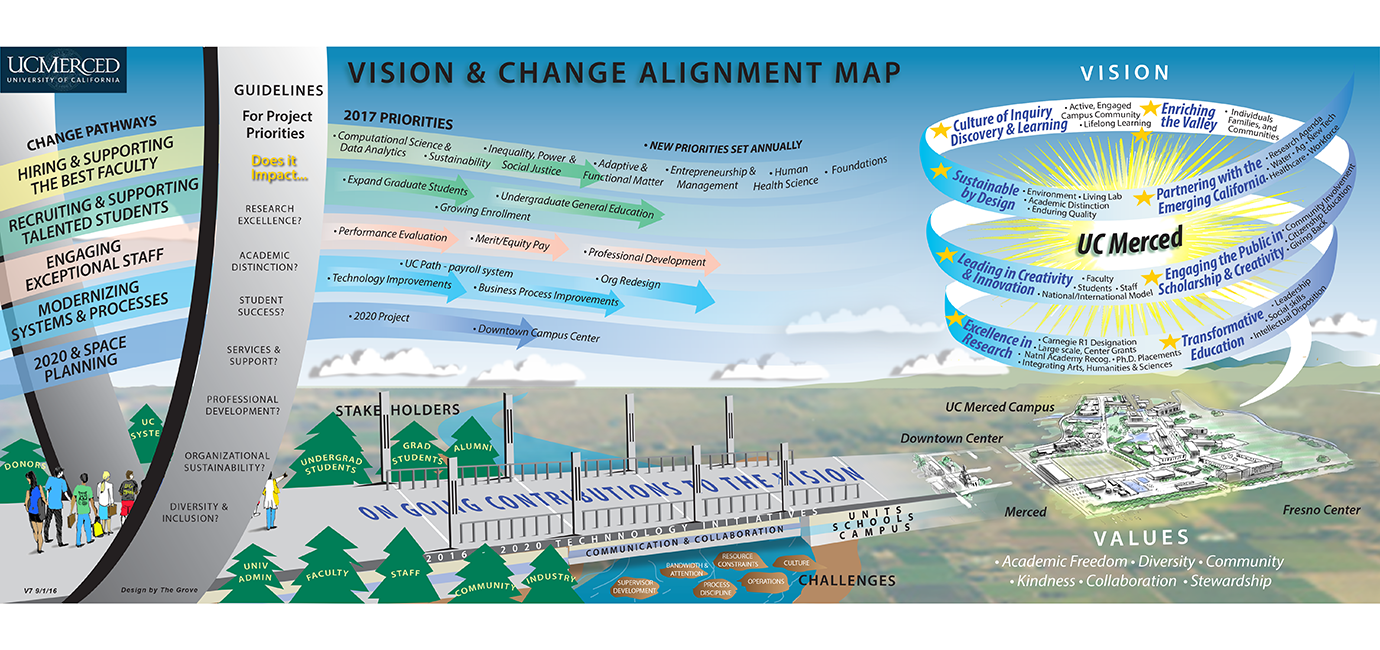

My “training,” or should I say first experiences with OD, were at OD Network conferences in the 1970s. I didn’t know what the field was back then but found out about it when trying to hire Sandra Florstedt for our Coro Leadership program in San Francisco. She worked at Kaiser as an OD Practitioner and explained to me OD was an application of behavioral science theory for organizations, working to see the whole organization as a living organism and creating conditions that would allow people to find solutions to their own problems from within. I remember her telling a story about early practitioners drawing on the work of biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy, crediting him with founding general systems theory. He was trying to understand open systems in nature. She also shared about Kurt Lewin, a German who helped found social psychology, arguing that a values orientation and democratic processes were critical to achieving planned change. I had been working to get Coro Fellows to understand the city as a whole system and Lewin’s advocacy of action learning and group dialogue was inspiring. Sandra subsequently introduced me to the OD Network conference at Snowmass in 1976 where I presented about Arthur M. Young’s Theory of Process and Group Graphics and became a practicing member of the network.

Evolving a Personal Perspective on OD

The seed idea of seeing organizations as living systems, and seeing change as a social process quickly put down roots in my work as I began to develop a practice. Initial work as a graphic facilitator evolved to supporting teams and developing the Drexler/Sibbet Team Performance Model, then learning and facilitating strategic planning with Rob Eskridge and Ed Claassen, and now doing change consulting and multi-stakeholder processes on large systems. My current work with Gisela Wendling and The Grove’s new Global Learning & Exchange Network (GLEN) is living at the edge of inquiry into collaborative methodology. It is all driving back to the seed thought that open, living systems need different kinds of support than machines. In the process my quilt of understanding pulled in ideas from complexity theory, cognitive psychology, social constructionism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Earth Wisdom practices. And always, tracking the tension and sometimes polarization between a materialistic and a holistic way of thinking about organizations and change.

Still Thinking About Whole Systems

My graphic work is inherently about making systemic sense out of people’s thinking, so the seed impulse for OD is still strong, but I’ve reached out to other thinkers beyond the field of OD.

I’ve been personally deeply inspired by the holistic work of Arthur M. Young’s Theory of Process. He didn’t deal with organizations, but as a cosmologist set out to reconcile the knowing from metaphysics with the best findings of physics and mathematics. He was a systemic thinker through and through, but insisted that purpose and process are more fundamental than objective structure, though purpose and process need these structures to express themselves.

I also discovered that researchers in complexity sciences support his orientation, finding that living systems organize around flows of energy from which structures emerge and embrace open, not closed, rule sets for interaction. Flows include money, information, constituencies, climate, and people themselves.

This process orientation has led to my paying attention to Frederick Laloix’s Reinventing Organizations , inspired by Spiral Dynamics, an orientation that is developmental at its core. It’s popular in Europe and leading people to experiment with much less hierarchical organizations out of trust that if people are taken seriously, they can manage and solve problems in a more “emergent” way. (There are missing elements I will explore in later writing). I also think that Theory “U” in its inclusive embrace of spirit, soul, mind and body is a clearly process oriented methodology that is very compelling.

Past Reflections, CURRENT EDGES

As the crises rising from climate change and accompanying mass migrations accelerate, I can’t help but believe that a huge amount of adaptation and change will be required in the future. People could (and are) reverting to  fear-driven authoritarianism, simplistic, bunkered responses but might also be (and are) called to step up to higher level of collaboration. It’s not a given. What will support this second option?

fear-driven authoritarianism, simplistic, bunkered responses but might also be (and are) called to step up to higher level of collaboration. It’s not a given. What will support this second option?

Will the lessons from neuroscience and social psychology about brain biases and hi-jack reactions help practitioners create safe spaces for collaborative co-creation of new alternatives and avoid numbing and dissociation?

Will reclaiming the role of ritual and ceremony and traditional practices bring nourishment and feeling into systems wrung out with efficiency? (My current life partner, Gisela’s, work on liminality and change is now recasting many of my assumptions about traditional OD approaches as I see how shut down people become without attention to the inner process of change or the creativity that lies in the in-between spaces where cultures meet.)

Will learning from Earth-wisdom practices and indigenous methods help restore our connection to nature and each other?

Under it all I wonder if somehow we can transform the deeply entrenched materialistic paradigm into something that respects relationship and spirit as much as objective truths? Can we reclaim an anchoring in core values that are deeply moral?

The original thinking of the founders of OD reflect many of these perspectives, reacting as they were to the trauma of world wars. But methods birthed in humanism have become canonized and abstracted to a degree that some of the original curiosity and experimentation gets lost. There are exceptions. Lisa Kimball, a pioneer in computer conferencing and former OD thought leader, advocated an approach called Liberating Structures that deliberately mixes and matches different modalities to stimulate new awareness and jump out of siloed thinking. Bob Marshak and Gervase Bushe surveyed many new OD approaches is their book, Dialogic OD:The Theory and Practice of Transformational Change. They see World Café, Open Space, Future Search Conferences, The Art of Convening, and other high engagement methods focusing more on new narratives and emergent, generative imagery than on diagnostic processes.

Are Organizations Even the Right Focus?

But deep down I’m personally awakening to the possibility that organizations may not be the most relevant focus for those of us who work for and within organizations. Today people and organizations are so interconnected and interdependent— embedded in overlapping networks and consortia, fields of practice, value webs, and a booming world of free agents—amid constant change—that “context” may be a more important frame for attention. And by context, I mean much more than paying attention to customers and constituents. It includes the environment, cultures and their values, other sectors and organizations, and larger social networks and relationships.

Some of my current GLEN colleagues’ are working explicitly with energetic fields and collective intelligence, using the learning from neuroscience to create “safe” environments for engagement and using design thinking for social change. Philanthropic organizations are funding for collective impact, asking for NGOs to cooperate and collaborate in facing important issues. Multisector collaborations and networks are arising to face systemic issues. The adaptation requirements of global warming will force us all into levels of reinvention we’ve never even imagined, well beyond nicely bounded organizations.

I also wonder how my and others’ years of focusing on “the organization” has contributed to our field supporting many organizations just becoming better at maximizing the extraction of value from people and the land and avoiding responsibility for impacts, and completely ignoring context.

What if OD Were…

So, wrapped in this quilt of reflection, I wrote out my own definition for a field of OD that I could live into.

“The field of Organization Development is inspired by the question of how to support human systems that are alive, evolving, and more like true ecosystems than mechanisms, although they depend on these for expression.

We help leaders, teams, organizations, communities, and larger networks learn to connect with purpose, motivate themselves to act, find appropriate processes to guide collaboration and co-creation, and create results that both improve the effectiveness of their organizations and contribute to the quality of their communities and the Earth as a whole..

We are not afraid of the complexity and inquiry required to respond to these questions. We learn by doing and do to learn. We continue to seek out and test theory that helps our clients make connections in the midst of turbulence and fragmentation. We are capable of being, at heart, a community of practitioners, schools, and networks believing that humans have only just begun to tap the full potential of people working together for the common good.”

I want to be part of a future in a field that differentiates itself not by the value of its answers for organizations alone, but by the depth and sensitivity of its questions in service of the whole.

share this reflection, and to share my hope for the future of the field. I’m not writing a history of OD, but of the quilt of understanding that provides me with direction as a process consultant, and might be useful to other practitioners who work in or with organizations.

share this reflection, and to share my hope for the future of the field. I’m not writing a history of OD, but of the quilt of understanding that provides me with direction as a process consultant, and might be useful to other practitioners who work in or with organizations. fear-driven authoritarianism, simplistic, bunkered responses but might also be (and are) called to step up to higher level of collaboration. It’s not a given. What will support this second option?

fear-driven authoritarianism, simplistic, bunkered responses but might also be (and are) called to step up to higher level of collaboration. It’s not a given. What will support this second option?

Coming back to the United States from a month in Europe has my head spinning. Gisela and I were working in Germany, Austria, Italy and Poland, leading our Visual Consulting: Designing & Leading Change

Coming back to the United States from a month in Europe has my head spinning. Gisela and I were working in Germany, Austria, Italy and Poland, leading our Visual Consulting: Designing & Leading Change