Jan 08, 2026

I just finished watching the Thinking Game, a 2024 Tribeca Festival selection about Demis Hassabis, CEO of Deep Mind and Nobel winner for his work on AI and folded proteins. The acceleration in AGI hopefulness was in its pitch of acceleration at that time this documentary was produced, in no small part to Deep Mind having mastered video gaming, go, and then folded proteins. Google’s early support was important or course. And now the game is on in ways even Hassabis might not have anticipated.

As recent experiences with hallucinations, scamming, the environmental and economic costs of data centers, and the thought of cyber war mount people are beginning to seriously question the bubble. But AI is here. I think Hassabis is right saying that AI is like the development of electricity itself or possibly fire. The world is not turning back.

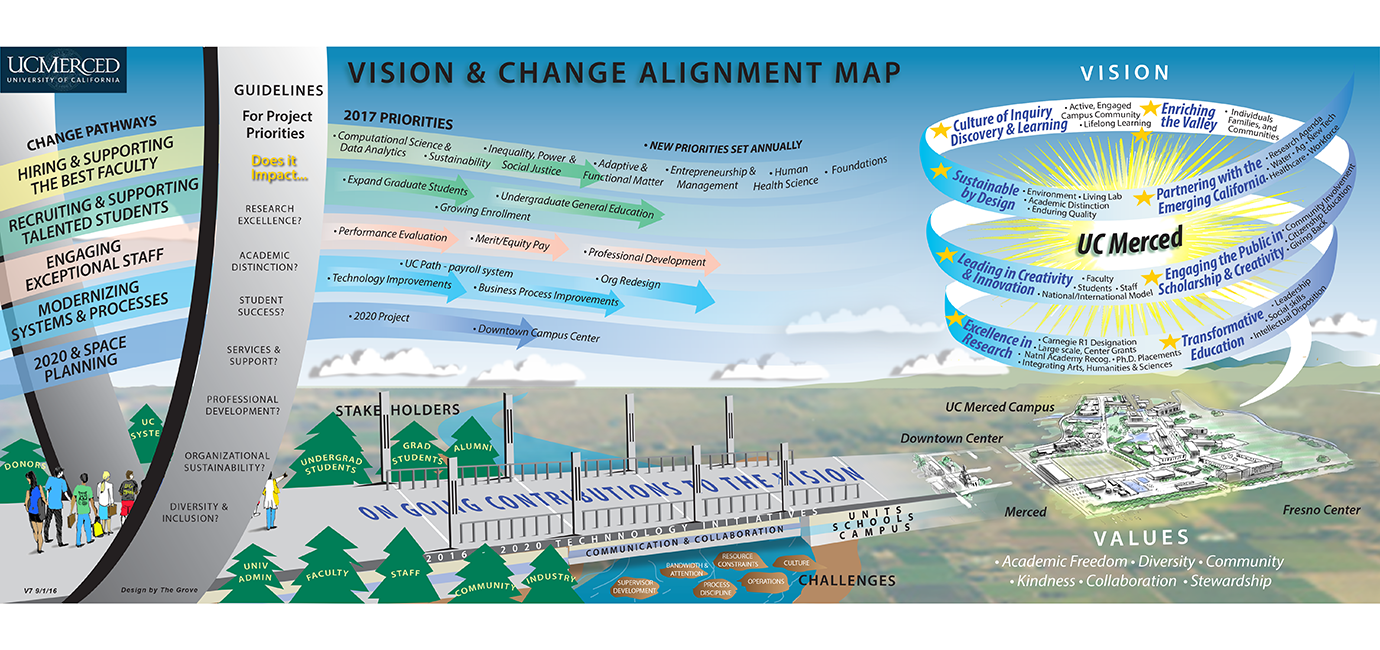

AI has been on my mind as I enter a period of contemplation about what I will do now that I’m retired from active graphic facilitation. My life partner Gisela Wendling is CEO of The Grove now and we are heading into leadership development, coaching and transformational change work. Of course, we are using the many tools I and The Grove team have developed over the years. But the world of process consulting has already changed. Organizations are not supporting the face-to-face processes upon which we developed our business. Hybrid work grows steadily, and now AI is catalyzing questions across the boards about how work is going to get done now that knowledge workers are in the cross hairs of big tech.

It occurs to me that I am one of those knowledge workers. Working across public, private and non-profit sectors all over the world graphically mapping out people’s thinking and studying the ways people make sense of their organizations, I’ve developed a deep appreciation of archetypal patterns and the metaphors that allow people to appreciate systemic-level phenomena. And focusing all this “knowing” on AI I’ve some thoughts I’d like to share.

I come at this thinking game looking through the lens of an old pyramid diagram that illustrates data at the base, then information, then knowledge, then wisdom at the tip of the pyramid. I remember talking with Jacob Needleman, a philosopher and author I had the honor to work with, about how people had already lost the distinction between information and knowledge. “Knowledge is knowing what to do with information,” he said. The colloquial meaning would be “know-how.” Wisdom was truth. Given this definition I found it annoying to have complex information called “knowledge” by the high tech industry.

It makes sense to me that people looking to predict the developmental arc of AI see workers as moving into the evaluation and reviewer/editor roles and away from the first draft creators. These oversight roles rely on field experience, understanding context and all the things about people that machines don’t know or “feel.” I don’t think original creators are obsolete, but the workaday pumping out of everyday information will shift for sure and already is. Our own teams at The Grove use chat to get a start on writing.

But the wisdom tip of the triangle also fascinates me, especially as I get older. I’ve come to think that the kind of “truth” wisdom represents isn’t information, but knowing that arises in context. It is the response of Solomon to the two mothers arguing over who should have the baby. “Why not cut it in half?” Of course, the true mother would not agree to that. Deeply discerning responses to others within specific contexts is where wisdom appears.

So, I personally don’t think I’ll be in the AI crosshairs directly, but our society is. As I track the way AI is skillfully luring young people into screen time, or generating convincing pharmaceutical scams, or poised to weaponize pathogens I worry.

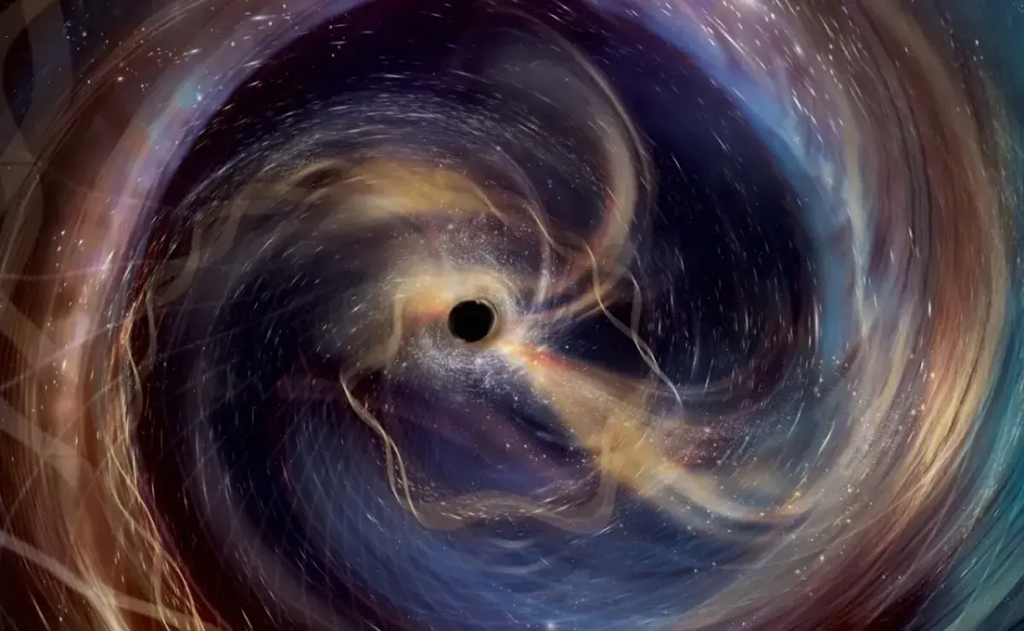

Two metaphors describing this have jumped out recently. One was provided by Paul Saffo, a well-known Silicon Valley forecaster that I worked with for ten years at The Institute for the Future in Palo Alto. In a recent talk to law students at Stanford (he has three lay degrees and is register for the bar in California and New York, although never practiced law) he characterized the challenge they would be facing in conceiving of what kind of law, and he asserts, international law, will be needed to provide order to this new world of AI augmented organizations and governments. “AI is a solvent that is leaching our society,” he claimed. “The old order is broken.” The metaphor stopped me. What does he mean by leaching? Could it be our contextually linked knowledge! Could it be our relationships themselves?

I remember back in college reading general critiques of the technologization of the modern world, and how at root the idea that processes and procedures can be taken out of context and transplanted is at the root of many ills. Classical Newtonian science sees the world as material and only connected through direct bonds and physical interface. At this physical level technology has been a marvel. Applied as it is now to all human activity the result is chilling. It’s denial of consciousness and the shock of scientists having created the atom bomb drove Arthur M. Young to spend a lifetime of work articulating a cosmology that brought consciousness back into the scientific paradigm.

My own emerging metaphor is that AI is to knowledge what white bread is to nutrition. It is processed thinking. It has all the sugars and carbs but loses many of nutrients that come from comes from the sharing of whole grain living through writing and the arts.

It’s timely that the dictionary publisher Merium-Webster chose the word “slop” as the term of the year. I personally find myself using AI for research about what is generally known on a subject, but I’ve noticed that being presented with seven pages and three dozen bulleted lists puts a burden back on me to make sense of things in usable writing.

The other day, while digging into the role of mycelia in forest ecologies for a novel I’m writing, Chat GPT politely asked if I wanted to have some suggestions for dialogue between several of the characters. “NO” I responded. “I want the fun of writing the dialogue myself, for my ear, from my understanding.” In its programmed, sycophantic style, it complemented me on that choice. I wondered how many writers will choose to stay with their own voices.

I haven’t experimented with AI “friends” and coaches yet, or adult entertainment, or trying to game the financial markets but it’s all happening right now. Why am I thinking “circus?” Dare I imagine the end of democracy and rule by the tech masters and their AI?

As for myself, I’m going to concentrate my creative work on sharing some whole grain stories from my own lived experience so we don’t forget what human life tastes like.

It started in Eckernförde, Germany, a fishing port and resort town on the Baltic Sea almost in Denmark. Its name means “squirrel” the name of an old fort there, and low German for fjord. The week we were there was glorious. A sunny departure from the overcast, rainy July. Being a seaport there were many sea gulls, our guests on the long walks along the Baltic to the old downtown. As is my custom, I wanted a small symbol of this trip that I could keep in my studio. We found a small shop that had little seagulls sitting on piers. Perfect!

It started in Eckernförde, Germany, a fishing port and resort town on the Baltic Sea almost in Denmark. Its name means “squirrel” the name of an old fort there, and low German for fjord. The week we were there was glorious. A sunny departure from the overcast, rainy July. Being a seaport there were many sea gulls, our guests on the long walks along the Baltic to the old downtown. As is my custom, I wanted a small symbol of this trip that I could keep in my studio. We found a small shop that had little seagulls sitting on piers. Perfect!